Monsters, with David Livingstone Smith

About the Guest

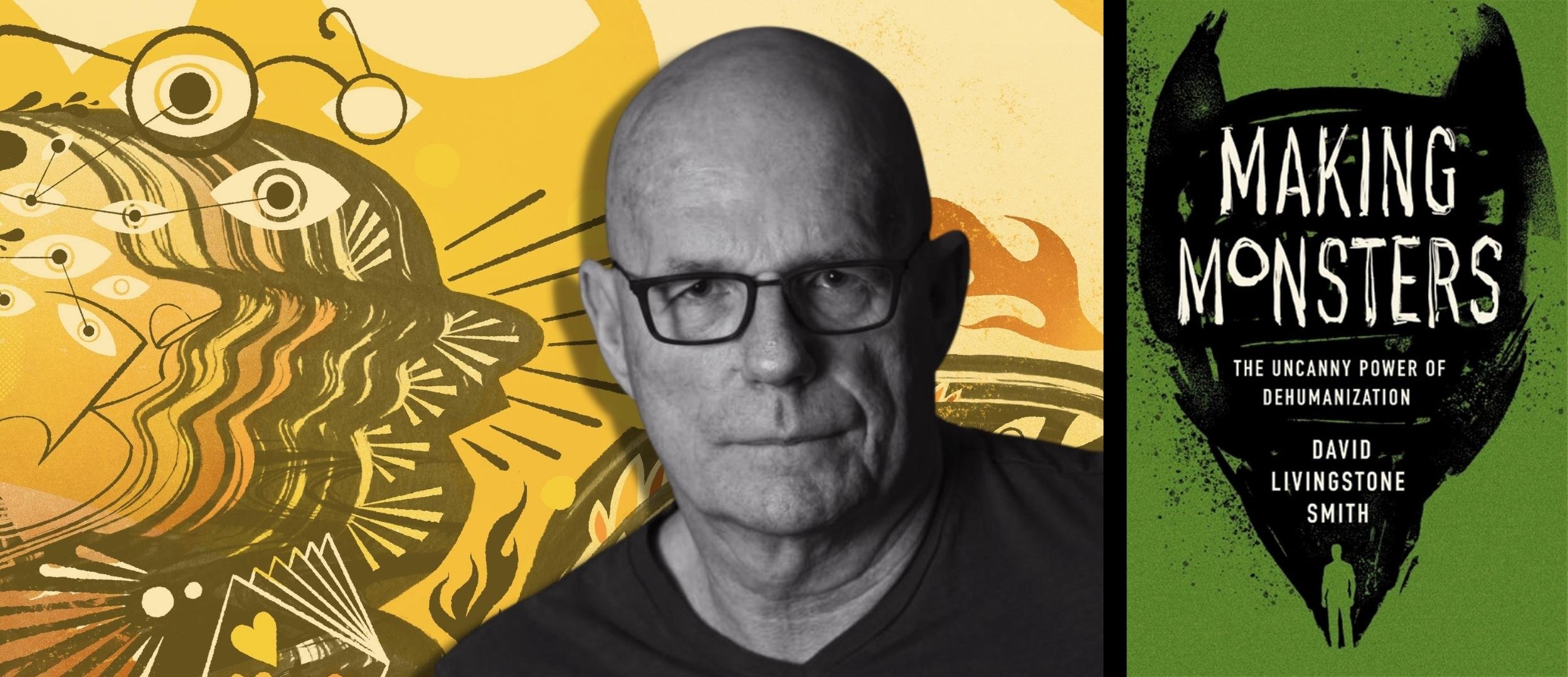

David Livingstone Smith is Professor of Philosophy at the University of New England in Maine. His latest book is Making Monsters: The Uncanny Power of Dehumanization. Other books include On Inhumanity and the award-winning Less Than Human. Learn more about his work at davidlivingstonesmith.com.

Best Books

Making Monsters: The Uncanny Power of Dehumanization, by David Livingstone Smith.

The Interpretation of Dreams, by Sigmund Freud.

Transcript

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: We are all vulnerable to the dehumanizing impulse.

BLAIR HODGES: For decades, David Livingstone Smith has studied dehumanization. He's spent a lot of time researching horrific genocides, lynching, massacres, and other brutalities. His latest book emotionally drained me because it deals with some of the most inhumane things people do to each other. Real humans pull the trigger. Real humans administer the poisonous gasses and drop the bombs. People not entirely unlike me and you, although it's a lot more comforting to imagine they're monsters, too. But then, in fighting monsters, we risk becoming the very thing we’re fighting against.

On this episode of Fireside with Blair Hodges we're talking with David Livingstone Smith about his book, Making Monsters: The Uncanny Power of Dehumanization.

Writing about stomach-turning topics – 1:06

BLAIR HODGES: David Livingstone Smith, welcome to Fireside. It's great to have you here.

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: Oh, thank you, Blair. It's great to be here with you.

BLAIR HODGES: I'm excited to talk about your book Making Monsters. This is a new book from Harvard University Press.

But before we get into definitions of dehumanization and some of the specifics, I'd like to ask at the beginning what it was like for you to write this book. Because as I was reading it, it brought up a lot of emotions for me. This was an emotional book to read. There were moments that shocked me, moments that disgusted me, I felt despair sometimes.

And, you know, reading some of the examples you write about, where humans are committing unbelievable atrocities—So if it was like that, for me, as a reader, I wondered what it was like for you as a researcher and a writer to spend so much time with that material.

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: Well, I'm kind of used to it. I've been working on dehumanization for, I don't know, fifteen, sixteen years, and one gets accustomed to it. As I imagine, say, a surgeon gets accustomed to cutting into human bodies, or an oncologist gets accustomed to the awfulness of cancer.

BLAIR HODGES: At the beginning was it like that? Did you have a period when you had to really wrestle with things? For example, I spoke with someone who wrote a book about a massacre, and they would actually have nightmares at the beginning of the process.

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: Yeah, it never gave me nightmares. But it was, I think, the best way to put it, is a deeply transformative experience, digging into these things. And not only reading these very explicit accounts, but writing these very explicit accounts.

And I think that explicitness is really, really important. It's important for me to get my readers to understand that these things need to be taken very, very, very seriously. So in a way, I want my reader to have difficulty reading the book.

BLAIR HODGES: Why did you choose this topic to begin with? It’s, again, not the sunniest topic. So how did you get to dehumanization?

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: Well, as I say to my students, I don't do sweetness and light. I can answer that question in two ways. There are two components. One is autobiographical.

So I grew up in the fifties and sixties in the Deep South, which was, of course, the tail end of the Jim Crow era, and the level of racial oppression—it was palpable, it was explicit. There were no dog whistles or anything. You know, people lamented the fading away of the Ku Klux Klan and things like that. The poverty, the segregation.

But I wasn't acculturated into southern culture. My family moved down to Florida when I was a young child, and I lived in an extended family with my maternal grandparents, both of whom were Jewish refugees from Eastern Europe. And my grandmother in particular—although she had to leave school in her teens to help support the family, she was deeply knowledgeable about the history of antisemitism, genocide of Native Americans, and the oppression of African Americans in this country. And so she educated me to some extent, and helped me to understand the world I was living with—living in, I'm sorry, down there.

And that left a real deep mark on me, because if you're not acculturated into that particular brand of southern culture, as a child you just can't help thinking, “This is terrible. This is something incredibly wrong.” So I've carried that experience with me through my life.

Much later, around about 2006, I was finishing writing a book about war in human nature. And in the course of the research I was doing for that book, I came across all this dehumanizing wartime propaganda, where enemies are represented as vicious predators or game animals to be killed for sport, and so on. And I thought to myself, gosh, this is very interesting, I need to learn more about this, and I found the literature was extraordinarily limited. So a friend convinced me. He said, “David, yeah, you've got to write a book on this. This has got to be your next book.”

And so I did. That was what prompted me to write my 2011 book, Less Than Human, and I've been working on that topic ever since. So there's this sort of confluence between my academic research and really early formative experiences in my life that led me to this topic.

BLAIR HODGES: This is a little beside the point. But have you heard of the British show Black Mirror?

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: Oh, I've seen that episode.

BLAIR HODGES: Okay. “Men Against Fire” is the name of it? Yeah. Where they sort of come up with this way to change so that soldiers view the enemy—and they're called roaches, and they look like monsters. They actually change their visage.

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: Yeah.

BLAIR HODGES: So that that came to mind as I was reading this book.

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: Yes. I mean, it's hard for me to believe that the writer of that episode hadn't encountered my first dehumanization book.

Defining dehumanization – 5:57

BLAIR HODGES: Yeah, I recommend that episode. It basically, you know, it makes soldiers feel more comfortable with killing someone and we'll talk about this a little bit later on—whether it's normal or natural, if humans have to resist that, you know, how people in war work. So we'll talk about that.

So with your background in mind, let's go ahead and define dehumanization. How does your book define it?

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: Okay, so that's very important. It's an important question, because the word “dehumanization” is used in so many different ways, and it often generates more heat than light because of its ambiguity. People use the word “dehumanization” to refer to, basically, any bad thing that human beings are subjected to.

The way I use the word “dehumanization” is to denote an attitude—the attitude of conceiving of other members of our species as subhuman creatures. And I chose those words very, very carefully. So the “attitude,” that means it's in your head, you know, you can demonize others without ever persecuting them or, or harming them. And “subhuman creatures,” rather than, say, subhuman animals. Because very often—and particularly in the most dangerous and toxic forms of dehumanization—the dehumanized people are thought of as demonic or monstrous beings, not simply as vermin, or predatory beasts, or whatever.

BLAIR HODGES: And so the book talks about this conception of it, which is, “what is dehumanization,” but you also talk about a theory of how it works psychologically. So there's kind of two things happening in the book of defining what dehumanization is, but also making a case for how it actually works. And that seems to be where a lot of the scholarly disagreement happens, really on both of those things. I mean, the definition you come up with will affect how you define how it works, I guess.

For example, some theorists have suggested that dehumanization is a kind of disengagement—like it helps turn moral inhibitions off, so we're more likely to act in horrible ways to something because we've eliminated any qualms about it, like they're not a person, this is a thing, so it can be treated poorly or horribly. But you kind of suggest that the opposite can be true, that there's actually a kind of extreme moral engagement that's happening with dehumanization.

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: Yeah. So dehumanization certainly does turn off inhibitions. I don't characterize them as moral inhibitions, I think they're actually deeper than that. See, the thing is, I argue in the book, drawing on a number of other scholars, that actually most of us find it really difficult to do serious, sub-lethal, and certainly lethal, harm to others.

And we find that difficult because of the sort of beings that we are—we're highly social beings. And all social animals have to have inhibitions against harming members of their communities because, you know, there's no way you can carry on to social existence if you're at each other's throats. And we, being what biologists call “ultra-social,” have to have very, very strong inhibitions against this sort of harm. And dehumanization is one gimmick that human beings have developed to turn those inhibitions off, to selectively turn them off, in order to do harm to others.

But in addition to turning the inhibitions off, dehumanization is motivating. And it's typically motivating in a highly moralistic way. So this idea of “dehumanization equals moral disengagement,” which goes back to early research into dehumanization in the fifties and sixties—I don't agree with that. People who dehumanize others in the most lethal ways—that is, the ways that lead to say genocidal violence—often see what they're doing in highly, highly moralistic terms. Certainly, every genocide that I've studied, and I've studied quite a few, those perpetrators of atrocity see themselves as ridding the world of some terrible evil. So it's a highly moralistic mindset.

BLAIR HODGES: That really stood out to me, because I had previously thought the way those early researchers did, which is, dehumanization is a way just to make us morally disengage. But what I realized is, that's because I'm coming to it, looking at the actions those people are taking, as being immoral.

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: Yeah.

BLAIR HODGES: Like hurting another being, another human, as an immoral thing. And so that must mean that they're not acting morally, when the more scary thing is that they're, to them, acting very morally, that there's almost a moral obligation, or they generate that moral obligation, which makes dehumanization even more frightening and more powerful.

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: Yeah. And of course, it implies that when we slip into that way of thinking of others, part of the baggage that goes along with that is we think we're absolutely justified and righteous in our activities.

Mindset and attitude versus action – 10:46

BLAIR HODGES: Do you think—some people would also say you can dehumanize someone without intending to, or without having even subconscious beliefs about that. What's your thought about that? Does dehumanization have to include the thinking and reasoning that goes along with it, or can we also dehumanize others just by looking at the outcome, or that what actions we’re actually taking can be dehumanizing, even apart from our intentions?

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: So I think there are a couple of issues here. I'll tackle the second one first. As we discussed right at the beginning of this conversation, the term “dehumanization” is used in lots of different ways. In my account, actions aren't dehumanizing.

If you want to call actions dehumanizing within my framework, they're only dehumanizing in a derivative sense. That is, they're actions flowing from dehumanizing attitudes. But actions per se can be cruel, they can be horrific, they can be, you know—the commission of atrocities. But I reserve the term “dehumanization” for the mindset that very often, but not inevitably, produces such actions.

BLAIR HODGES: And why is that important to you? Why preserve that difference?

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: Well, with all of these morally serious topics—dehumanization, sexism, homophobia, ableism, racism, so the way I like to put it is “dehumanization and its neighbors,” I think it's important that we're very, very clear and specific about what we're talking about. Because, surely, the purpose of studying these things is to do something about them. Right?

BLAIR HODGES: Mmhmm.

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: So I don't just want to theorize about dehumanization. I want to theorize towards an end—that is, to generate enough knowledge, or to inspire others to correct my errors and generate enough knowledge, to be able to have the tools to constrain or to prevent this sort of thing. And muddying the waters by using the term “dehumanization” to refer to two different things—action and attitude—I think, I think is unhelpful in that respect.

Now, you might think, “Well, why? [laughs] Maybe they belong together.” Well, the fact is that so called dehumanizing actions can perfectly well be committed without the dehumanizing mindset. You don't have to dehumanize people to harm them, to torture them, to exterminate them, and so on. Dehumanization helps, but there are other ways of short circuiting our inhibitions against these horrific acts. So—

BLAIR HODGES: What's an example of other short-circuiting?

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: Oh. Well, historically, let's see, the use of intoxicants was one.

BLAIR HODGES: Okay. Yeah, drugs, they would give soldiers drugs or—

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: Drugs, alcohol, that goes back to pre-history.

BLAIR HODGES: Okay.

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: Mind altering rituals. Certain forms of religious ideology. And even the development of long-range weapons, where the perpetrator is not confronted with those cues that would cause them to inhibit.

BLAIR HODGES: You're not seeing the gore.

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: Yeah.

BLAIR HODGES: You don't look into someone's eyes.

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: You're not seeing, you're not smelling, you're not hearing, you're dropping a bomb, and you're just not exposed to those phenomena.

BLAIR HODGES: Okay. Now, we can circle back. Sorry to take you on a little side path, there.

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: No, that's fine.

BLAIR HODGES: Now we can go back to—You’d said the second thing, now you can say the first thing.

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: Yeah. So dehumanization should be understood, not as something that's deliberate. Dehumanization happens to us, right? So it's not the case that we think, “Oh gosh, how can I harm these people? Oh, I know! [laughs] I'll convince myself that they're not really people!” That could never work, right?

BLAIR HODGES: Right.

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: Because we'd always be on to the effects of—

BLAIR HODGES: The fiction.

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: —the deception that we're perpetrating on ourselves. Propagandists, however, can take that cynical attitude. They can induce in us—

BLAIR HODGES: To get other people to believe—

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: Yeah, exactly. Exactly right.

So dehumanization happens to us, and therefore, we slip into it in response, typically, to dehumanizing propaganda, under certain circumstances. There are circumstances that make us more vulnerable to that propaganda than would otherwise be the case.

So what that implies is that we are all vulnerable to the dehumanizing impulse, right? It's very easy to think, “Oh, no, if I were in Germany in 1941, I wouldn't have supported the extermination of the Jews,” right, easy to say. But with the right forces bearing down on almost all of us, we slip into that state of mind.

Skeptics of dehumanization – 15:13

BLAIR HODGES: And you also mention that some scholars are actually skeptical that dehumanization is even a real thing. What's an example of that? Why would anybody say, “Oh, I don’t actually think dehumanization is real”?

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: Well, there are some compelling reasons to be skeptical of dehumanization. I don't accept them. But the argument is important. And in fact, the argument—the specific argument that's been around for a number of years now, that dehumanization isn't real, really motivated me to improve the theory of dehumanization that I presented in my 2011 book, Less Than Human.

BLAIR HODGES: Yes, I should tell people, this book is almost an add on—you had a book in 2011, and then you're like, “Oh, okay, we gotta go again.” So this—

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: That's right, and if I write another one, I'm sure it'll be the same. Because— [laughter]

BLAIR HODGES: So what was that? Like, what was that thing that was like, “Ooh, I need to address that in another whole book”?

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: Okay, so the person most associated with this critique of the dehumanization concept nowadays is a philosopher named Kate Manne. She has a chapter on dehumanization in her influential book Down Girl: The Logic of Misogyny.

BLAIR HODGES: She also blurbed your new book, by the way, I should say!

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: She did. She did. We've been in an ongoing dialogue for years. She's a really, really good philosopher.

So Manne's skepticism is based on the fact that, if we actually look at examples of dehumanization—say historical examples, we find what is sort of a contradiction, that although the ostensible dehumanizer refers to those whom they dehumanize as vermin, or beasts, or monsters, or demons, they also refer to them in, and behave towards them in, ways that are only fitting for the treatment of human beings.

So for instance, in the Rwanda genocide—as in many genocides, by the way—mass rape was a tool of war. Militant Hutu would rape Tutsi women specifically and explicitly to humiliate them before killing them. Now, you don't humiliate vermin, right? That makes no sense at all. So, although the in Hutu propaganda Tutsi were referred to as cockroaches and hyenas and snakes, humiliation doesn't apply to any of those sorts of beings. It applies specifically to human beings.

Similarly, suppose you encountered a rat in your home [laughs]. You wouldn't say to the rat, “You're nothing but a rat,” right? That only makes sense if you're aware that you're talking to a human being and want to degrade or demote them from human status.

Now, this can be taken much further than Manne does. Because in fact, if we look at historical examples of dehumanization, we find the dehumanizer not simply implicitly acknowledging the humanity of their victims, but often explicitly doing so. For instance, by referring to them as “criminals.” Again, there aren't any criminal rats.

BLAIR HODGES: Yeah, a rat can't be a criminal.

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: Or in the space of a single sentence, describing them as subhuman and human.

BLAIR HODGES: Yes, like “That person is subhuman.” Well, you just said they're a person—

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: Exactly, exactly. That is so common—

BLAIR HODGES: And you show this in accounts. Yeah. You have quotes from Nazis who were being interviewed about what they were doing during the war, or people during the Rwandan genocide, and they'll still slip back and forth between attributing personhood to the people they hurt, and also saying, “Well, there's they were subhuman,” or “we saw them as subhuman.”

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: That's right. Exactly.

BLAIR HODGES: And so Kate Manne would say, “Dehumanization can't really exist, this is actually just sort of a smokescreen, or an excuse, or just a metaphorical way of explaining atrocity.”

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: Yeah. So, reconstructing her argument, as I see it, it's something like this: Well, there's a contradiction there. Logically speaking, you can't think of someone as simultaneously all human and all sub-human.

BLAIR HODGES: Right.

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: In addition to that, the notion that dehumanizers literally do see those whom they dehumanize as less than human beings is pretty weird, right?

BLAIR HODGES: Yeah.

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: So the conclusion you can derive from that is “Well, you know, dehumanizing rhetoric is just rhetoric, it doesn't reflect actual beliefs about others.” And you can see the appeal of that argument.

I don't think it's correct, though. I think that, in the first place, human beings are perfectly capable of sustaining contradictions, contradictory beliefs. In fact, it's something we all do. I'm a philosophy professor—one of the things you learned studying philosophy is, you're committed to contradictions [laughter], which you hadn't realized before. There's a difference between psychological phenomena and logical regulations, as it were, right?

So our human psychology is such that I think we can sustain these contradictions. And indeed, I think we do, when we dehumanize others. That in fact, when people dehumanize others, they see them as human and subhuman at once, simultaneously. Logically impossible, but psychologically possible. And that strange juxtaposition is vital for understanding how the dehumanization works.

Essentialism and race – 20:14

BLAIR HODGES: I think that gets to the idea of essentialism, which your chapter four talks about. It's the idea of like, what makes any thing a particular thing? What makes a horse a horse? Is it the fact that it has four legs and a head and runs? Because that could be—many things could be a horse. Like, what is horse-ness? Right? What is personness? What are the essentials?

And you show in the book, all the way back to Aristotle and the idea of humans having a rational soul, and then religion and Christianity adopted that, to this immortal soul, and then scientific thinking had the discovery of the genome, and then social constructs like race. So you show how all these different people throughout time are trying to get at what the essence of humanness is, like, what it means to be human. But when we do that, we start we start categorizing and ranking things, right?

So this is where racism and race become really important parts of your story. Americans and Western Europeans came to strongly associate skin color and other phenotype traits—like your shape of your nose, or your forehead, or things like this, the length of your arms, with race, they were making up this idea of race, and its appearance based.

But because of this idea of “essences,” you're also showing how humans came to also see, “Oh, actually, there can be something about a person that's hidden behind what their appearance is,” right? Talk about that a little bit—this idea of essentialism, and how race plays into that.

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: Okay, so there are two sort of intersecting things here, which are vital for understanding dehumanization, and racism, and other phenomena. One is, as you say, essentialism.

So the term essentialism, kind of like dehumanization, is all over the map. I use it in a particular way, and it's a way that psychologists use it. Back in 1989, there was a very influential paper published called “Psychological Essentialism.” And it kicked off a whole, very robust, research mini-industry in psychology. And the claim in the paper was really twofold.

That we human beings have a tendency, a disposition, to carve the natural world up into kinds of things, like biological species, for instance.

And we are inclined to see membership in any of these species as due to an unobservable inner something, which they called the “essence.” So for instance, what makes a porcupine? Well, it's not the appearance of the porcupine, according to this way of thinking, which we all tend to engage in, it's not having sharp quills and having four legs and being sort of grayish brown, and so on. And it's obvious that we don't think of it that way. Because of course, you could have a mutant porcupine lacking all of those characteristics, and we still regard it as a porcupine. Well, what is it? Well, something in some strange way on the inside that makes it a porcupine, where “inside” is meant in a very peculiar sense, right?

BLAIR HODGES: Yeah, because where is it?

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: Yeah, it's not like an internal organ.

BLAIR HODGES: Yeah, what is it? What is that inside?

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: That's right. Now this is a very powerful disposition. And as you mentioned, throughout history, when people have tried to make sense of what it is to be human, they've engaged in essentialistic thinking, and it comes really shockingly naturally to us.

My favorite example of this, or one of my favorite examples, was the idea—which became a church doctrine at the fourth Lateran Council in 1215—that the sacramental host is literally the body of Christ, and the body of Christ is in every crumb of the host. Now, how can you make sense of that? Well, it certainly doesn't look like, you know, [laughs] the wafer doesn't look like a Palestinian Jew, right?

BLAIR HODGES: Right.

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: It looks like a cracker.

BLAIR HODGES: And if they had a microscope, they could look at it even microscopically, and see that—

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: Exactly. It's it seems very, very different. However, the philosophical idea here was, “Well, that's merely its appearance.”

BLAIR HODGES: Right.

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: “But its essence through the miracle of Transubstantiation is the body of Christ.” And you know, people can accept that. And if we didn't have these essentialistic tendencies, we would just find it extraordinarily incomprehensible.

So yeah, so it came to be over time that various candidates were suggested for the human essence—that inside property that makes us human beings: the rational soul, the Christian soul, somewhat later the idea of humanness was in the flesh or in the blood, and then in the genome.

BLAIR HODGES: I can see the logic of the latter, because whether a thing can reproduce with another thing seems to be a pretty easy way to say, “Oh, they are of the same, they're the same kind of thing. Because these things can reproduce together.”

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: The problem is that the genetics of any species must be variable. If that weren't the case, then evolution couldn't happen. But essentialism establishes rigid boundaries between kinds. So you either have the essence, or you lack it. In fact, those people who invoke the genome as the human essence are generally people either who haven't thought through essentialism very carefully, or who don't know anything about genetics.

So I mean, that's the essentialist idea. And that's super important for dehumanization because it helps us solve a problem. And that problem is, anyone who dehumanizes another must recognize that in all outward respects, the dehumanized person is indistinguishable from a human being, right? [laughs] I mean, the Nazis had to put yellow stars on Jewish people to distinguish them from Aryans, so—

BLAIR HODGES: And you could have a Jew who was six-foot blond hair blue eyed, and—

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: That's me. Yeah, that's me! [laughs] I had blonde hair. I have blue eyes, and I'm six feet three inches tall. I could almost be one of Hitler's bodyguards. But I would have been regarded as a mischling, a mongrel of the first degree, because I have a Jewish mother and a Gentile father.

So appearance isn't essence, right? The idea of essentialism allows, like with the case of the porcupine, that appearance and essence can come apart. And that explains how this kind of dehumanization is possible. How a Nazi officer could look, say, at me and say, “Yeah, well, he looks like an ordinary human being, but he's really a counterfeit human being. If you look at his genealogy, he is really, on the inside, a subhuman, and it's what’s on the inside that counts.”

We see this, similarly, in the treatment of enslaved people, say, in Barbados in the seventeenth century—and I quote some documentation in the book, that enslaved Africans were thought to have a human form, but lack a human soul. And because they lacked the human soul—and of course, souls are invisible so you can get away with saying whatever you want about that—

Hierarchical thinking – 27:06

BLAIR HODGES: Yeah, you can't prove it.

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: You can't prove it, yeah [laughs], souls are by definition unobservable. So they were, as the Reverend Morgan Godwin—who's one of the interesting characters in the book—he said they were “ranked among the brute beasts” and treated as such. He was a campaigner against the dehumanization of Africans and Native Americans, he was an interesting guy. So that's the essentialism bit.

But just the idea of essentialism doesn't give us an idea of subhumanity, of being less than human.

And here's where hierarchical thinking kicks in. So for a very long time, human beings have accepted the idea that the natural world is arranged as a hierarchy, with the most perfect beings at the top and the least perfect at the bottom. In the Middle Ages, this is often referred to as “the great chain of being.” In Europe, in Christian Europe, you know, God was at the top, the supremely perfect being, and then you had archangels and angels, and we modestly placed ourselves just below the angels. And then every other kind of organism occupies a rank lower, lower, lower down, till you get to inanimate matter. And this was connected to intrinsic value. So the higher a thing is in the hierarchy, the greater intrinsic value it has, the more it matters, the more its life matters, and so on.

And this immediately gives us the notion of subhumanity—anything ranked below the human is subhuman. Now, if you look at diagrams from the Middle Ages, this is quite explicit [laughs]. You know, there are pictures of the great chain, of labels on the various ranks.

Historians of ideas, I think, have gotten a couple of things wrong about this, though. One is that it's a uniquely European notion. It's not, we find it all over the world. Not everywhere, but in many, many, many places. And secondly, it hasn't disappeared. I mean, the classic accounts says, “Well, it faded away in the late 18th, early 19th century.” That's not true at all. It's still part of us. If an irritating fly were buzzing around your studio, and you swatted it, and I suppose, said in horror, “How could you do that to a fly?” I mean, your response would quite naturally be, “Well it's just a fly, man. Come on.” [laughter] So it's ranked low, right?

BLAIR HODGES: Yeah.

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: Now, neither essentialism nor hierarchical thinking are scientifically respectable notions, right?

BLAIR HODGES: Yeah, say why, though, because I think this is a really important point. It seems so obvious that I would say, of course, a fly would matter less or be—and there are a few people that disagree, like Hindus that have ahimsa, the principle of like, never harming anything. So they wear veils over their mouths and shuffle their feet so they don't like step on creatures.

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: Yeah, yeah.

BLAIR HODGES: So it just seems like, well, of course! Of course this being is better than this one. But you're saying, “Actually, there's no scientific—we can't prove that.”

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: Right. I mean, it could be true, but it's not science that tells us this, right? Science doesn't have the notion of one kind of being better or of greater value than another kind of being. And ever since Darwin, the idea that evolution is an ascending scale of perfection has been abandoned—or officially abandoned, because even biologists can't help being hierarchical. And they use terms like “higher” evolved and “lower” evolved—

BLAIR HODGES: Right.

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: —you know, higher and lower organisms, which makes no Darwinian sense. In fact, Darwin once wrote to a colleague, “Never used the terms higher and lower.” The Darwinian worldview is more that every kind of organism is just really, really good at doing its thing. And we should look at the world of living things sort of horizontally rather than vertically.

BLAIR HODGES: And there's also a lot of genetic overlap, and some supposedly lesser beings are more genetically complicated and interesting on that level than humans are, so—

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: Yeah, that's absolutely true by any criteria. Like, if you're going to say, “Well, success is a mark of biological superiority.” Well, then the blue green algae have us beat by a long shot. We're very young species.

BLAIR HODGES: What about consciousness, though? We sort of place it with consciousness, the fact that we can reason. The fact that we're having this conversation would signal some sort of superiority.

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: Well, superiority in the ability to have conversations. But there are fish that can sense electrical fields. We can't do that! You know? [laughs]

BLAIR HODGES: Yeah, yeah.

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: We can't fly!

BLAIR HODGES: So again, it's interesting when you start to realize, we assign that value. That's a decision we make. That's something that we're doing.

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: We assign that value. Yeah. And I think it's very important that we do, right?

BLAIR HODGES: Yes.

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: And I think it's actually vital for the human way of life that we do. So I'm not dissing it. But I'm pointing out that it's something we fabricate and attribute, rather than something which is a self-evident feature of the natural world.

BLAIR HODGES: In part, because then we can look back at dehumanization and see how its process is working and see—we can reason against it, we can say, “here are some of the ways that makes that problematic.”

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: Yeah, absolutely true. And it's twofold. Really, without hierarchical thinking we simply couldn't have dehumanization, it would be impossible. But it's very hard to do without hierarchical thinking. And the reason for that is, say when you were talking about the devout Buddhist monks who sweep the pathway so they don't step on an insect because the idea is that killing any being is wrong. The fact is, we can't get along without killing.

BLAIR HODGES: No.

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: I call this “the problem of killing.”

BLAIR HODGES: Our bodies are doing it all the time. [laughs]

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: Yeah, our bodies are doing it all the time. We have to eat, we can't just live on fruit. Even, you know, committed vegans kill carrots, Carrots are living things.

BLAIR HODGES: Sure.

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: It's always been the case that we have killed and exploited other organisms. Life feeds on life. That's part of what it is to be an animal, to feed on other life.

Now, but we're also—like I mentioned before—highly social beings, and we have to have inhibitions against killing our own community members. And because we're highly social, we are inclined to have very, very extended notions of our community. And it's been since prehistory. It's not like the community is only the local group. Human beings have traded, over hundreds and hundreds of miles, with other groups, for thousands, tens of thousands of years. And being human beings, we have to justify our way of life by finding reasons.

Now, one way we've developed this—which has really taken hold, one way we've justified what's killable and what isn't killable is through this idea of hierarchy. So in developing the idea of subhumanity, what we've done is we've essentially made it permissible, given ourselves reason why it's permissible, to kill certain beings, but not other beings, and more specifically, not members of our own kind. And because of that impermissibility, then, we've had to find the ways around it when we've regarded it as advantageous to kill members of our own kind. Dehumanization, the use of drugs, the use of certain religious ideologies, and so on.

The uncanny power of dehumanization – 34:14

BLAIR HODGES: That's David Livingstone Smith. He's a professor of philosophy at the University of New England in Maine. And we're talking about his book Making Monsters: The Uncanny Power of Dehumanization.

The “uncanny” power, that word uncanny doesn't just mean weird. There's a meaning there. Let's unpack that. Let's talk about the uncanny part of this.

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: Okay. Let's go back to when I was talking about how when we dehumanize others, we see them as simultaneously human and subhuman. That has a very distinctive psychological effect. And to understand that psychological effect, we have to look at the literature on—sometimes explicitly, sometimes implicitly—on what's frequently called the uncanny.

So the seminal paper on this was published in 1906 by a German psychiatrist named Ernst Jentsch, and it's called “On the Psychology of The Uncanny.” Now, uncanny, obviously, if it's a German paper uncanny is a translation. The German word is unheimlich, and what Jentsch meant by unheimlich was a little bit different from the way we often use the word uncanny in English—something that's uncanny can be just remarkable.

BLAIR HODGES: Yeah, unbelievable!

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: Highly unusual. All right. Like, “This is an uncannily good podcast that you do, Blair.”

BLAIR HODGES: [laughs] It's uncanny! Thank you.

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: But unheimlich—although unheimlich can be used in that sort of way, the core sense that certainly Jentsch had in mind is something like creepy, disturbing, eerie, and, at the extreme, horrifying.

So Jentsch was trying to figure out, what is it that elicits this sort of creepiness response in us? Why do certain experiences, certain perceptions, creep us out? For instance, to use one of his examples, going into a wax museum and seeing realistic human figures. Let's say you go into wax museum and there is a figure of, of George Bush, and it's well done, you look at it, and it's almost like you're seeing the guy there standing. But then as you look, you see—

BLAIR HODGES: But!

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: —it's a little bit off, right? It's, it's not quite there. It doesn't move, it doesn't breathe, its eyes look dead, its skin looks waxy. It's when that happens, Jentsch suggests, that our minds are torn between seeing this as a person and seeing it as an inanimate thing—a lump of wax sculpted into the form of a person. And as long as we can't totally move towards one alternative or the other, this elicits this disturbing sense. This sense of the uncanny, the unheimlich, the creepy.

He actually adds that such a realistic looking thing—say an automaton that looks like a human being and that moves—is even more disturbing.

BLAIR HODGES: Yeah, like the Hall of Presidents at Disneyland where—.

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: Yeah, exactly.

BLAIR HODGES: —the robot Presidents stand up.

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: It's nightmarish! Right?

BLAIR HODGES: [laughs] Yeah! The first time I was introduced to this was the idea of “the uncanny valley,” it was the Polar Express movie came out—

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: Yeah.

BLAIR HODGES: —and it was computer animated. And they almost looked real. It was like, almost! Which, I've seen plenty of animated films in my life, and I never had this feeling of unsettledness. But when I saw The Polar Express, I was really creeped out by the animation!

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: [laughs] Right. Exactly.

BLAIR HODGES: Because it was like, just close enough to creep me out. Not close enough to be real, but close enough to make me go, "Hmmm."

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: It's a famous example. It's supposed to be this, you know, heartwarming Christmas thing, right? [laughter]

BLAIR HODGES: Yeah!

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: It's like a nightmare. So you can see that Jentsch is on the territory which sort of intersects with the idea that when we dehumanize others, we see them as simultaneously human and subhuman.

It's like having your mind torn between seeing the figure in the wax museum as human and inanimate. You can see how Jentsch is thinking of having the mind torn between incompatible alternatives. Entertaining both is sort of in the same territory as my claim about dehumanization—that when we dehumanize others, we see them as human and subhuman, simultaneously.

In 1966 the anthropologist Mary Douglas publishes an influential book called Purity and Danger. It's about the idea of ritual and cleanliness, basically. And she argues that all cultures have this idea of the “natural order,” different kinds of things that—And, you know, everything can be placed in one of these conceptual boxes. But whenever you do this, there are some things that don't fit because nature isn't like that.

BLAIR HODGES: Yes, by the way, I was fully persuaded by her take on Leviticus and sort of the Law of Moses—distinctions of what foods you can eat and what you couldn’t eat? Because that never made sense to me until I read Mary Douglas.

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: Yeah, yeah!

BLAIR HODGES: I'm kind of convinced by her hypothesis of, “Oh, these are things that didn't fit into this natural animal and food hierarchies.” And so they were not natural, and so they were forbidden.

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: Yes, yes. So for instance, lobster isn’t kosher because well, it's like an insect, but it lives in the water like a fish. It's a shame actually, you know, she abandoned that analysis later on? And I don't think she should have. I think it's absolutely stunningly brilliant. And I can't see how you can properly make sense of the restrictions in Leviticus without that notion.

BLAIR HODGES: Yeah! It cuts across the lines so well, I was like, wow. It was like putting a pair of glasses on and seeing something come into focus.

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: Yeah, it's incredible.

So she says look, when something doesn't fit in—like the banned dietary stuff in Leviticus—it's experienced as disturbing, and dangerous, and needs to be specially handled, and embodying a kind of a disturbing power. And so something that doesn't fit in, that sort of transgresses these categories, well, that's kinda like Jentsch's view on the uncanny.

Then in 1970, we have the Uncanny Valley paper by Masahiro Mori, where he predicts that as robots become more and more and more human-like, we'll get more and more comfortable with them, until they're almost indistinguishable from humans, but not quite, and then we're going to get creeped out. And that sense of comfort is going to drop through the floor, and that's the uncanny valley. He uses a Japanese word bukimi, which is like unheimlich, it's creepy, It's eerie, it's disturbing.

And finally, the final bit of this, is the philosopher Noël Carroll, who wrote a wonderful book called The Philosophy of Horror, in which he looks at horror fiction. And one of the questions he asks is, “what makes a monster?” and he says there are two components.

So if we look at horror fiction, first of all monsters have to be physically dangerous—they want to kill you or damage you or something like that. They're not nice. But there are lots of physically dangerous things which aren't monsters. Monster has to have another very important property: it has to be an impossible combination of incompatible things. So for instance, one of his examples, zombies in horror movies—they're both alive and dead, simultaneously. You know, they're decaying corpses, but they eat human brains, and they walk around. Or a werewolf is a wolf and a human being simultaneously.

BLAIR HODGES: Vampire.

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: A vampire. Yeah. And vampire is actually a really cool example, because they're outwardly human, but inwardly non-human. So the essential—the essence and appearance dichotomy—

BLAIR HODGES: They can pass more than a zombie could.

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: Exactly, exactly. That line of thinking both addresses this problem of human and subhuman, and suggests that the way dehumanized people are regarded by those who dehumanize them has properties that are really quite different from just seeing them as, say, rats or lice or something like that, right?

Dehumanization, at least in the most toxic and most dangerous forms of dehumanization that I'm concerned about in Making Monsters, transforms human beings, in the eyes of their dehumanizers, into monstrous demonic beings, right along the lines that Carroll describes with respect to horror fiction.

And that explains a lot. I mean, it explains the incredible violence that flows from this sort of dehumanization—you're not compassionate to Count Dracula, right?

BLAIR HODGES: Yeah, you want to put a wooden stake through his heart.

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: The monster is evil.

BLAIR HODGES: Yeah.

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: And anything is acceptable in the battle against the monster or the monsters.

BLAIR HODGES: And when you've destroyed the monster, you can celebrate it like, Hooray!

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: Absolutely, yeah.

BLAIR HODGES: Which you point out, for example, with these lynching parties that would happen in the in the United States, where we have pictures of people being lynched and then huge crowds—

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: Huge crowds.

BLAIR HODGES: —of white people around smiling and kind of enjoying it like a picnic.

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: Yeah, yeah. No really, and body parts taken as souvenirs, and schools close so the kids could come and watch the lynching. And the lynching wasn't just an execution, it was often hours and hours of the most brutal torture imaginable before the victim was killed, often burnt alive.

Yeah, so the sort of moralistic component of dehumanization comes in here, because of course, the monster is evil, the monster must be destroyed because the monster is evil and the embodiment of evil.

BLAIR HODGES: It requires our response. And you lay this out in your last chapter, where there are different ways humans try to manage monsters, eliminate monsters, control monsters, avoid them. And there are rituals we use, like the lynching rituals.

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: Mmhmm, yeah.

BLAIR HODGES: This is where the rubber really meets the road in the book, is to connect the psychological thought processes we go through when we dehumanize with the actions we take as a result of those processes.

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: Yeah, absolutely.

Witnessing dehumanization while working on the book – 44:17

BLAIR HODGES: That's David Livingstone Smith, a professor of philosophy at the University of New England in Maine. And in addition to his latest book, Making Monsters he's also written a book called On Inhumanity, and also an award winning book called Less Than Human. You can learn more about his work at davidlivingstonesmith.com.

So David, did you see any examples of dehumanization happening in the news while you're writing this book that seems relevant?

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: Unfortunately, it's always happening in the news. So recent examples? Well, as your listeners may or may not know, India is ominously close to genocidal violence against Muslims by Hindu nationalists. And there's no doubt that dehumanization is playing a role in the anti-Muslim propaganda.

As it did in Myanmar, which is something I know much more about. The Rohingya, which were, are, a minority of a minority, have been characterized by radical Buddhist monks as reincarnations of a vermin. And then all the, you know, the standard dehumanization rhetoric.

So you mentioned race earlier, and I didn't address it. But when a group of people is racialized, is conceived of as belonging to a different race, there are some very, very common features. They're violent, they're dangerous, they're rapists. “We must protect our women from them.” They're parasites, and they're outbreeding us. And we found that all with the Rohingya. And all of that way of thinking, that's the road to dehumanization, right?

BLAIR HODGES: You mention in the book, too, some examples here in the United States. We can hear the testimony of police officers when they're talking about having shot a Black man. I don't remember—there's so many of them, I can't remember if it was Michael Brown or whether—

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: It was Michael Brown, yes.

BLAIR HODGES: But I've heard this time and again, where they're like, “Oh, this was this guy was a monster. He was about ready to go rage and just like tear my head off,” or something. This idea that a Black person has superhuman strength.

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: Yeah. The Jamaican scholar Sylvia Wynter talks about—I believe it's, if I remember correctly, Los Angeles police, referring to crimes in which the “Black on Black crimes” as “no humans involved.” And I think the dehumanization of African Americans, particularly African American males, is rampant in this country.

It's a little bit tricky, because explicitly dehumanizing discourse is still socially unacceptable. It had a little bit of a renaissance during the Trump regime—

BLAIR HODGES: Yeah, yeah, less so than I thought. But I think a lot of people—yeah, there are still taboos.

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: Yeah, so we have to make inferences. But say, the idea of “essential criminality,” which is certainly applied very frequently to, particularly to black males, is, I think, a secular version of, say, what you see in my chapter on the history of antisemitism, that these are demonic beings.

BLAIR HODGES: Yeah, it's important to point out that throughout the book—and people, as they read it, will see—you have examples in here of religious ideologies that feed dehumanization, scientific ideologies that feed dehumanization, political ideologies. This isn't a phenomenon that's restricted to the realm of religion or science, but is something we see—and your research has shown this, and other people's research—anywhere there's ranking and categorizing going on.

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: Yeah, and all of those fears can combat dehumanization as well as perpetrate it.

Hope in the fight against dehumanization – 47:45

BLAIR HODGES: Right. But I have to say, sometimes it seems like a bit of an impossible cause, because these are huge processes that are carrying on in individual experience and societal experiences. And so when I think about trying to make interventions and trying to prevent this—like how could I have, if I’d lived in Nazi Germany and happened to be in a particular family with particular connections and particular beliefs, how easy it could have been, how it could have been so possible for me to participate in that.

Dehumanization seems to be a huge, just a gigantic machine that's too big to break. And so I've just wondered what you think about that? Because you've been a scholar on this, but also an advocate on this. You were a guest at the G20 Summit in 2012, where you spoke on dehumanization. So I'm just interested in whether you have hope, and if you do, where it comes from, and what can we do about all this?

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: Well, I like to use Cornel West's phrase, I'm hopeful but not optimistic. You know? I write books because I really do want to change the world. And my influence is probably widest through writing because of the way I'm positioned as an academic. And no matter how small it is, you know, certainly what I do, and what you do, these are drops in the ocean. But if you get enough drops going, it makes a difference. And even if it's unlikely to work, we've got to give it our best shot, right? We try to do the right thing.

So in the first chapter of my 2020 book On Inhumanity: Demonization and How to Resist It, I tell my favorite Jewish joke. And that joke is about a village in Russia, a Jewish village, a shtetl. And there's one guy who is mentally disabled, he's apparently unemployable. But the rabbi decides he's going to find a job—everyone needs to be taken care of. So the rabbi gives him the following job. He's to sit on a chair in the outskirts of the village and wait for the Messiah to come. Which he does dutifully. Every day he drags his chair out and sits and stares into the distance waiting for the Messiah. And one day a visitor comes and meets him. Here he is entering the village and he sees this guy sitting in the chair. He says, “What are you doing?”

And the man, let's call him Shlomo, says, “Oh, I'm doing my job. I'm waiting for the Messiah. The pay is bad. The hours are long, but it's steady work.” [laughter]

And that's how I see what I'm doing. You know, it's steady work.

But there are, no, there are always things that can be done. I think one very important thing is understanding that we're all vulnerable to dehumanization, so we can track ourselves a little bit so we're less likely to slip into it. This is really an “know thyself” kind of thing. The temptation, of course, is to regard those who are responsible for atrocities as the subhumans, and we're okay. But I think that's exactly the wrong attitude.

BLAIR HODGES: Because it's the dehumanization itself that's the risk.

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: Exactly.

BLAIR HODGES: I remember when Osama bin Laden was killed, and I had such mixed feelings about this, about like—I saw people celebrating it and I felt like—I mean, I just felt very conflicted about it.

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: Yes, that's part of a big tragedy. Yeah, yeah. So we mustn't do that. In fact, we should see them as holding up a mirror to what we're capable of. So that's important. Historical education is important as well, because whoever we happen to be—you know, your nation, your ethnic group, your, your religious group, whatever—we all have blood on our hands historically. And that's very important for us all to understand. That we're not exempt. Our group is not exempt from atrocity. And that induces, hopefully, a measure of humility and a recognition that we might do it again, or maybe even we're doing it now. We haven't really taken that into account.

There's social and political action, you know, preserving the institutions that give us a modicum of protection—only a modicum, because all those institutions can be subverted. A free press can be subverted, you know, an independent judiciary can be subverted. But they're something right? They're something.

Very importantly, dehumanizing propaganda works best, I believe, by playing on a sense of vulnerability. In fact, I'm deeply influenced here by Sigmund Freud's Future of An Illusion, where he offers an account of the psychology of religious belief, which is basically that religion is the fulfillment—he's talking about the Abrahamic religions here, right—of the deepest, most powerful urges of humankind, and that is for deliverance from our vulnerability. Our vulnerability in the face of the forces of nature, which will do us in, and our deliverance from human injustice.

So, you know, as human beings deep down, we all understand—to use Freud's term, we all understand that we're helpless, and we have a yearning for salvation from that helplessness. And I think a lot of authoritarian politics plays on the yearning for salvation. That's why authoritarian politics has a quasi-religious character, you know? The authoritarian politician is like God: omniscient, omnibenevolent, omnipotent.

BLAIR HODGES: And will save you, even in the secular sense of just you'll be safe and happy—

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: —Will save you, yes, it will save you. But in order to save you, they need to make you feel like you need to be saved, and they need to play—and we find this in authoritarian propaganda—they play on the sense of vulnerability. So the more surplus vulnerability there is—the more people don't have enough to eat or don't have healthcare, or don't have jobs, you know, all the things that make us vulnerable—the more fuel there is for authoritarian propagandists to exploit our vulnerability, and to inculcate dehumanizing attitudes in us through their rhetoric. So basically, you know, I think social safety is really, really important.

And finally, because race, I argue, is intimately bound up in in dehumanization, and because, scientifically speaking, the notion of race is vacuous—it does not have scientific justification—if we could get rid of race, if we could get rid of the very concept of race, I think it would do a lot towards getting rid of dehumanization.

Ethnicity, race, diversity – 54:03

BLAIR HODGES: Is there a way to do that while also celebrating diversity and difference? Because some people want to say—the reason I push back a little bit there is because some people, especially white people, will say, “Just stop talking about race, just make it go away.” Like if everybody just stopped—

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: Yeah, that's—

BLAIR HODGES: And I don't think, I don't get the sense that's what you're talking about.

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: Not at all.

BLAIR HODGES: Because that would be a denial of difference and culture and some pretty significant things.

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: Well, stopping talking about something doesn't make it disappear any more than, you know, not using dehumanizing rhetoric in public makes it disappear. But the idea of race is not the same as diversity.

Let me give you an example. My wife is Jamaican. She's a philosopher too, by the way. She's Jamaican, the way we would describe her as a Jamaican of African appearance, and I'm an American of European appearance. Neither of those characterizations refer to race, right?

BLAIR HODGES: Right.

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: They refer to a phenotype and appearance. Well, why not refer to race? Well as a Jamaica—culturally speaking, and her sensibilities and her food preferences, in all of these respects, my spouse, Sabrina, is very different from an African American, or an Ethiopian, or a Cameroonian. Race lumps all these really diverse peoples together under one category and homogenizes them.

So I think, actually, the idea of race is the enemy of diversity. It's not the friend of diversity. And similarly with, you know, categories like White, there's a massive amount of diversity. Think of the Ukrainians that are fleeing the horrors being inflicted on them.

BLAIR HODGES: I mean, as you know, whiteness developed as a way to say, as a hierarchical way to elevate so-called White above—

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: That's right.

BLAIR HODGES: So you can trace historically that that whiteness is a historical construct in that way.

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: We can, yes. And to continue to, to affirm these categories is to continue to promote the white supremacist project that gave birth to them, in my view.

BLAIR HODGES: Yes. And I guess my vision would be like, I'm fine. I'm okay with race. I'm not okay with the with the ranking and hierarchical thinking that comes along with it. And as you said, the erasure that can happen with it as well. Asian is one example—

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: That's the most ridiculous category on the face of the Earth.

BLAIR HODGES: Yeah! It's like there's—it's a nonsense thing. Yeah. But having grown up here in Utah, being a white person not knowing a lot of people of different ethnicities and nationalities, just saying “Asian,” I mean, it's so easy to fall back in that kind of thinking.

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: Oh, yes it is.

BLAIR HODGES: But as you said, it can be an erasure. To me, it's got to be like, a recognition of the beauty of diversity, and, you know, that's kind of what I'm going for, whatever label we want to give it, it's an ending to this ongoing hierarchy that we build, that sets some people up over others—I mean, white people, frankly, above other people.

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: Yeah. That's true. But of course, one of the problems here is that the idea of race was birthed in hierarchy. And there's a huge historical legacy there, which is very, very hard to banish.

BLAIR HODGES: But here’s this, too: African Americans have a remarkable history and a well-earned identity, a pride in being Black because of the things they traveled through. And I guess I would want to find a way to honor that reality and to encourage culture to maintain a certain—there's a passage that they've gone through, and they continue to go through, you know, so—

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: Sure, as I would simply add, as African Americans. The ethnic categories, absolutely right on, but that's distinct from the racial fabric.

BLAIR HODGES: It's different, okay, gotcha. Okay, we spend a little bit extra time on that, but I think it's worth it.

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: It's very important.

BLAIR HODGES: Yeah, yeah. So all right, this is David Livingstone Smith. I encourage people to check out the book. I will say it's written by philosopher so it may seem a little dense, but really what Dr. Smith is doing is breaking down being really clear about the language he's using. And if you just spend a little bit of time with this, it really clarifies the way that you use language and I use language. It's Making Monsters: The Uncanny Power of Dehumanization, and we'll be right back to talk about best books with David Livingstone Smith.

[BREAK]

Best Books – 60:17

BLAIR HODGES: We're back with David Livingstone Smith. Today, we talked about Making Monsters: The Uncanny Power of Dehumanization. You can check out Dr. Smith's other works at his website, davidlivingstonesmith.com.

All right. It's best books time, David, and it's your turn to tell us what you brought.

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: Oh, well, you asked for a book that changed my life. And there are many books that have done that to a greater or lesser degree, but perhaps one of the most important ones—in fact, definitely one of the most important ones—was published in 1899, and the author is Sigmund Freud, and the book is The Interpretation of Dreams.

Oh, it's had a vast influence on me. You know, in my former career, I was a psychotherapist before I moved to philosophy. And even when I was doing my philosophy PhD, my dissertation was on Freud as a philosopher. So Sigmund Freud is always looking over my shoulder and a big influence on my writing.

And when you say that a lot of people think, “Oh, you're a Freudian! That’s all outdated.”

BLAIR HODGES: Right.

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: No, I'm not! I'm not a Freudian or any kind of “-ian,” you know, I just have immense respect for Freud's creativity and adventurousness and inquisitiveness as a thinker.

And one of the really nice things about The Interpretation of Dreams is, it not only gives you a radically novel and I think important take on how human beings work, but you can also use it to form a better relationship with yourself.

BLAIR HODGES: Even today? So picking it up today, you see it as not just an artifact that would give us some insight into Freud, but that it actually has some things in it that that you'd recommend to people?

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: Oh, yes, a lot! I think there remains a lot in Freud that's of use. And frankly, many of the people who dismiss Freud—which is most of the psychology profession—haven't bothered to educate themselves on Freud. We see this—you know, the token three pages in the Introduction to Personality textbook for undergraduate psychology majors. It's surprising how many errors can be squeezed into three pages.

But, you know, no one bothers to read this stuff. And I'm not saying there aren't really well-educated critics. There are. And a lot of that criticism is really, really, really good. The important thing is not to swallow Freud or any other thinker whole, but to reject what seems wrong and to make use of what seems right.

BLAIR HODGES: That's perfect for what this best book segment is trying to do, which is a reminder that there's some amazing stuff that has been published, and it's too easy to throw everything out as though it's outdated. Even for religions, to do the same with their scripture—either to think it's perfect or to think that it's useless.

And I think that too often we fall into those kinds of approaches to books. Another episode in this season talks about this with the book Jane Eyre. Should fourteen-year-old kids read Jane Eyre today because there's sexism and colonialism and these types of things and making a case that grappling with those things—along with the benefits that that book still offers—is a useful exercise. And it sounds like you feel the same about Freud, which is—

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: Yeah.

BLAIR HODGES: —this is a person who's really inspired you, has raised questions that matter and that still matter, has wrestled with them in creative ways that can spark greater creativity, and has reached insights that are still relevant, and some insights that aren't still relevant. And the point isn't to find perfection in past best books. The point is to find fellow thinkers and travelers in this life.

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: And sometimes it's really important to try and understand where writers have gone wrong.

BLAIR HODGES: Yeah!

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: That's often very illuminating. And often the mistakes that are made are what I would call “good” mistakes. They're, they're not cheap, they're not crummy mistakes.

BLAIR HODGES: Yeah.

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: And one can learn from the mistakes of others in that sort of way.

And by the way, the way you accurately characterize my appreciation for Freud, I think this applies to secular people with respect to religious texts. Although I'm an atheist, I think its religious education is incredibly important and sorely lacking. I don't think we can—there's so much of our world we simply cannot understand without understanding, well, in the first place, our own religious traditions and secondarily those of others.

BLAIR HODGES: I love that. Thank you so much. David, this has been such a great conversation, and there's a lot more we could have covered so I think people can check out Making Monsters and get a feel for it. But thank you so much for joining me at Fireside today.

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SMITH: Oh, thank you. It was a pleasure.

Outro – 64:53

BLAIR HODGES: Fireside with Blair Hodges is sponsored by the Howard W. Hunter Foundation—supporters of the Mormon Studies program at Claremont Graduate University in California. It’s also supported by the Dialogue Foundation. A proud part of the Dialogue Podcast Network.

Alright, another episode is in the books, the fire has dimmed, but the discussion continues. Join me on Twitter and Instagram, I’m at @podfireside. And I’m on Facebook as well. You can leave a comment at firesidepod.org. You can also email me questions, comments, or suggestions to blair@firesidepod.org. And please don’t forget to rate and review the show in Apple Podcasts if you haven’t already.

Fireside is recorded, produced, and edited by me, Blair Hodges, in Salt Lake City. Special thanks to my production assistants, Kate Davis and Camille Messick, and also thanks to Christie Frandsen, Matthew Bowman, and Kristen Ullrich Hodges.

Our theme music is “Great Light” by Deep Sea Diver, check out that excellent band at thisisdeepseadiver.com.

Fireside with Blair Hodges is the place to fan the flames of your curiosity about life, faith, culture, and more. See you next time.

[End]

NOTE: Transcripts have been lightly edited for readability.