Options, with Taylor Petrey

“Historians can’t predict, of course. Though I can say with confidence that there will be changes.”

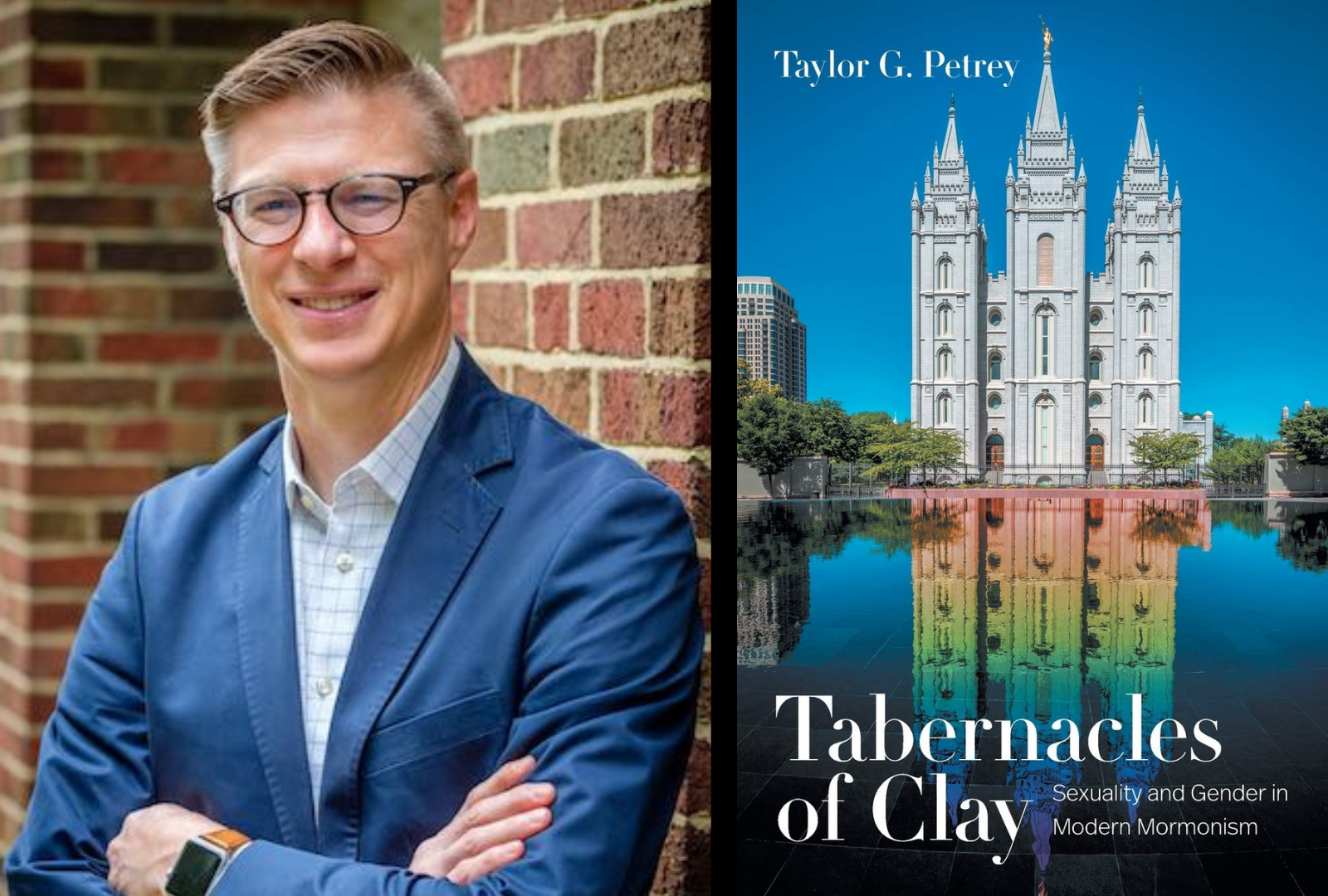

About the Guest

Taylor G. Petrey is associate professor of religion at Kalamazoo College and editor of Dialogue: a Journal of Mormon Thought. He received a Doctor of Theology and Masters of Theological Studies from Harvard Divinity School, and a BA in Philosophy and Religious Studies from Pace University. He is author of Tabernacles of Clay: Sexuality and Gender in Modern Mormonism.

Best Books

Tabernacles of Clay: Sexuality and Gender in Modern Mormonism, by Taylor Petrey.

Taylor recommended:

History of Sexuality: Volume One, by Michel Foucault.

Transcript

TAYLOR PETREY: Historians can't predict, of course. Though I can say with confidence that there will be changes.

BLAIR HODGES: Taylor Petrey was studying early Christianity at Harvard and he started to see a surprising variety of early Christian views about sex and gender. So much was up for grabs. And for Petrey, that ancient history made him wonder about current changes in his own religious tradition.

TAYLOR PETREY: You know, as a Latter-day Saint these were issues that everybody was just kind of talking and thinking about, they were issues that were affecting people's families, people's lives, people's marriages.

BLAIR HODGES: Current Latter-day Saint doctrine states that gender is an eternal human characteristic. But when Petrey started digging in the Mormon archives, he found other options.

TAYLOR PETREY: It turns out that not that long ago, Latter-day Saint leaders actually had a very different view, putting forward this idea that before we were born it wasn't necessarily the case that we were male and female, that we maybe had some choice or discretion in the matter.

BLAIR HODGES: That idea didn't stick around. But it kind of makes you wonder: what else was up for grabs?

Welcome back to Fireside with Blair Hodges. Taylor Petrey joins us in this episode to discuss his book Tabernacles of Clay: Sexuality and Gender in Modern Mormonism. It covers the fascinating twists and turns in Latter-day Saint thought about the proper role of women and men, the origin and proper response to homosexuality, and more. And by looking back, we might get a clearer view of what's up ahead.

TAYLOR PETREY: It's difficult to say what changes we're going to see in the future. I think that we can kind of look over those last seventy year period that I cover in the book and draw a number of different lessons and possibilities of things that the Church might do.

BLAIR HODGES: This is episode ten. Options.

Where the project came from

BLAIR HODGES: Taylor Petrey. Welcome to Fireside. It's nice to have you here.

TAYLOR PETREY: Thank you Blair. It's a great pleasure to be here.

BLAIR HODGES: We're talking about your book Tabernacles of Clay: Sexuality and Gender in Modern Mormonism. And I thought we just begin with the standard question of why you began to do this topic, how this became a book?

TAYLOR PETREY: Well, it was a little bit of an accident. I never intended to write a book on LDS history. I didn't intend to get into this subject area. I kind of fell into it. In part, maybe I felt impelled to do it. You know, I was a graduate student in the 2000s, and the Church was, of course, getting involved in national same-sex marriage issues during that time period. And it was the kind of thing that everybody was talking about.

And I was thinking about it as a graduate student. I thought, you know, I'll maybe just have one thing to say. I wrote one article about it in 2011, and thought that would be the last thing I would do. And then I just kind of kept coming back, and back again, to the topic and feeling like somebody needs to write a history. And I expected one of the really wonderful, great historians out there to kind of take this up. And I kept looking around, looking around for someone to do it. And I finally found myself in the mirror and was like, well, why don't you do it? So that's how it happened. [laughter]

BLAIR HODGES: So this is a book that talks about gender roles, men and women, it talks about sexuality, it talks about LGBTQ issues. And as you said, you published that first article and it's been a decade now, it's been ten years. Have you seen a lot of change over that time? What's your perspective on the overall scope?

TAYLOR PETREY: Yeah, in some respects, not much has changed in the Church. The Church still very strongly opposes same-sex marriage. It's made a few minor accommodations around some issues with sexual identity, gender identity, and a few things along those lines. The Church has changed on a couple of things around its political stances during the last decade.

But the larger cultural context has really shifted. You know, even ten years ago, a majority of Americans still opposed same-sex marriage. The tide was turning for sure, but once same-sex marriage was finally legalized in 2015 all around the country, that really kind of pushed it over the edge. And I don't know what the numbers are right now. But they were well over 70% not that long ago. And that's a huge dramatic shift for the context that the Church finds itself in. So though the Church hasn't changed that much, members of the Church and nonmembers of the Church definitely see this issue very differently than they did even just a decade ago.

BLAIR HODGES: How about members of the Church in regard to same-sex marriage? Have those numbers gone up as well?

TAYLOR PETREY: They have, and we don't have—I don't have at least—access to the most recent numbers. But even as recently as just a few years ago, a majority of younger members of the Church, of millennial members, did not have opposition to homosexuality, to same-sex marriage. That didn't necessarily mean that they wanted it to change in the Church. But at least their social attitudes had dramatically shifted.

Older members of the Church, still, a majority oppose same-sex marriage and homosexuality in culture, though even those numbers were dropping as time moved on. And so I suspect that if we were to do polls today that we would see even sharper increases among younger Latter-Day Saints and their attitudes on this issue that are a divergence with what senior leadership of the Church, where they might be.

BLAIR HODGES: I’m a member of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, and my own views have shifted on this over the past ten or fifteen years as well. So I feel like I've been traveling through this history myself.

And speaking of background, you as well, let's talk a little bit about your background, people that have listened to Fireside might recognize your voice from some of the little commercial spots we have. You're the editor of Dialogue: a Journal of Mormon Thought, and you have a Latter-day Saint background. Talk a little bit about that, and how that affected this project.

TAYLOR PETREY: Yeah, I think in part, this is how I got involved in the project to begin with. My original academic training is actually in early Christianity. And I was writing and thinking about gender studies in relationship to early Christian sources and history. But of course, as a Latter-day Saint over the last twenty years or more, these were issues that, again, everybody was just kind of talking and thinking about, they were issues that were affecting people's families, people's lives, people's marriages. And you know, I just felt drawn to the topic, I guess, and thought, well, maybe I've got something to say about it, given my other training in Religious Studies and in gender studies.

And so I came to the field of Mormon studies really in some ways as an outsider, as somebody not trained in it, but as a Latter-day Saint who is familiar with the sort of basic context of vocabulary, the personalities and so on. And so I really had to work hard to kind of train myself in contemporary history and in American history, those kinds of things that I didn't really have any immediate background in. But hopefully the end product shined some new light onto things that maybe other people had missed.

BLAIR HODGES: Do you think being a practicing member of the Church affected the way you approached the project or the kind of questions you asked?

TAYLOR PETREY: I don't know. It's interesting. I think as a scholar of religion we're so used to sort of approaching our subject area from a certain set of methodological standpoints that it doesn't necessarily matter if you're inside or outside. I think my familiarity as an insider certainly helped my initial sort of understanding, again, of the lay of the land.

But I don't know. I don't know, maybe other people would have an opinion on it looking at me from the outside. But I don't know if it necessarily affected the kind of analysis. It's the reason why I took up the project to begin with, you know. It was something that was important to me. Because of that I had a sort of personal connection to it. But I don't know if I would say that it affected the analysis, or that it sort of drove the outcome in some way.

BLAIR HODGES: I know from when I’ve talked to scholars of religion who practice a religion that they've done work on, they sometimes feel pressure—and this happens within Mormon studies, but it happens in other areas as well, where people within the tradition really want the scholar to arbitrate truth, they want the scholar to get into whether a religion is true or false or right or wrong. And those aren't really the questions that scholars tend to ask.

TAYLOR PETREY: Yeah, I think so. Perhaps the sort of person-on-the-street expectation of what a scholar of religion might do is to arbitrate truth or something. And really, what we're trying to do is explain things and to understand, to sort of even have a sympathetic approach to making sense of what's going on.

That doesn't mean that you can't disagree or agree, and scholars of religion, privately and publicly, will often do that. But the primary goal is not necessarily to again, say, yes, this is right, or this is wrong, but to say, here's what's going on, here's why people were thinking this, and here were the issues that were sort of informing their approach.

Marriage and racial purity

BLAIR HODGES: Well, let's dig into chapter one here. This book deals a lot with LGBT issues. But it also zooms out broader than that. So here in chapter one, it's called "Pure Marriage," and you take readers to the early 1900s, you don't go all the way back to the beginning of the Church. You go to the early 1900s, when you say that Mormonism was really interested at this time, in racial purity and gender purity during this time

Let's start with racial purity. What were Latter-day Saint leaders talking about at this time when it comes to race, and gender, and sex?

TAYLOR PETREY: I didn't initially intend to start the book there when I was conceiving of it. I was thinking about writing a history of sexuality of the Latter-day Saint tradition, and thought, well of course I'll have to talk about polygamy, and there were these big changes that were happening there. And that, you know, the last time the Church had really changed its teachings on marriage and the family where the shifts from polygamy to monogamy.

But as I was getting into the research, I really discovered that the more recent, and maybe in some ways, much more important change that the Church had with respect to marriage and sexuality had to do with their teachings on race and interracial marriage, and to sort of look at the changes that the Church's teachings on marriage with respect to race had on sort of shaping a lot of the later trajectory of the Church up until today.

Church leaders took an interest in what they were calling and thinking of as “racial purity” in the 1950s and 1960s, and sort of monitoring and maintaining those boundaries between the races because they believed in sort of racial lineages as divinely ordained. These were broader doctrines of American Christianity, that Latter-day Saints sort of adopted into their own understanding, and had been very, very crucial to the nineteenth and early twentieth century notions of Mormonism—these kinds of ideas of these cursed lineages or these blessed lineages, and the Church was in search of those who were descended from these blessed lineages and so on.

These sort of doctrines of blood and lineage and descent were so important that again, they were kind of affecting the way that the Church talked and thought about marriage and sexuality. And one of the major reasons they opposed interracial marriage was because of this idea that there were lineages that needed to be sort of kept pure from one another. And that's an interrelated idea to the same kinds of things that they were saying about gender during this time period—that gender also needed to be maintained as pure and that the intermingling of the sexes, when men became more like women or women became more like men, was going to sort of frustrate the divine design, the divine intent for the world in some way.

And so I tried to think about the doctrines about race and the doctrines about gender as joint ideologies that were emerging in the middle of the twentieth century, and that really dominated the way that the Church structured its teachings, its public policy, and the practices that they were engaging in in the Church itself, the sort of programs that they were creating during that time period.

BLAIR HODGES: And Latter-day Saints, and especially Latter-day Saint leaders, shared a lot of views with people who weren't Latter-day Saints. In the book here, you're quoting from a Virginia judge, Leon Bazile. I don't know if I'm pronouncing that right. But this is in the Loving vs. Virginia case about interracial marriage where this judge says, "the Almighty God created the races, white, black, yellow, malay and red. The fact that he separated the races shows that he did not intend for the racist to mix."

And Latter-day Saint leaders shared these ideas. J. Reuben Clark, for example, called interracial marriage “a wicked virus” in 1946. So this wasn't just about preference or taste or anything. They actually rooted this in God’s will, that mixing particular races was literally against God.

TAYLOR PETREY: That's right. And there are later views that emerge in the Church that try to soften or walk away from those perspectives until they're eventually abandoned. Although I think that they still linger in certain sections of the Church.

BLAIR HODGES: Where would you say they linger at?

TAYLOR PETREY: Well, I don't want to get too specific [laughs]—

BLAIR HODGES: Do it!

TAYLOR PETREY: —but certain regions maybe in the country where interracial marriage or racial attitudes in the Church maybe still lag behind the broader American culture. And there's a kind of holding on to maybe some of these older ideas.

Modern Church leaders don't teach these things. They haven't, they haven't said anything explicitly about interracial marriage in decades. Some of the senior apostles are in interracial marriages, you know, we really see have seen, I think, a sea change in some respects in the Church. But I don't want to ever say that these ideas have gone away completely, because many members of the Church report in their personal experiences, and again, in different regions and so on, that these attitudes do persist based on some of these older teachings.

BLAIR HODGES: I know as recently as a few years ago—and it may very well still be there—I know there was a marriage and family textbook or a book on the Church's official website that discouraged interracial marriage as recently as a few years ago. And again, it might still be there. I haven't looked it up.

But you kind of trace that shift away from saying that it was God's will, to more social concerns. This is what you say happened with Spencer W. Kimball in the seventies, they changed the discourse away from “This is God's will” or “this is an abomination,” over to, “it's not a very good idea, because it might cause problems.”

TAYLOR PETREY: There was a kind of general softening of the Church's teachings on race in general, and especially with respect to interracial marriage—from the fifties and sixties to the seventies—where we originally see these ideas, the opposition to interracial marriage, as a doctrine, as a divinely ordained and unchangeable thing, to then sort of being downgraded to wise counsel.

And Spencer W. Kimball is a key figure in this transition. And he puts out a teaching in 1976 that he says, we discourage it because you're coming from different backgrounds, and those marriages are less stable, you know, so he's trying to put forward kind of some secular arguments for it, rather than saying it's sort of, you know, the divine will here.

And fortunately, that's a little bit again of a softening of that doctrine. Unfortunately, this sort of wise counsel, discouraging interracial marriage teaching is precisely the thing that kind of persists in Latter-day Saint culture. That quote from Spencer W. Kimball has been reprinted many, many times, as you said, you know, very recently, even up—the last time I checked, it was in the 2015 or 2016 Young Men's instruction manual for the Church.

And so we do still see, again, the persistence of that advice of being put forward, not as a doctrine anymore, but as counsel. And of course, many, many people are objecting to that and have been, you know, advocating to get the that quote, you know, stop being reprinted again and again. But yes, it does. Those attitudes do persist and sometimes appear in official Church teachings.

Marriage and gender purity

BLAIR HODGES: Alright, so we see that shift in racial purity in this chapter. The other thing you cover, as I mentioned earlier, is gender purity. And after World War II, you talk about how national ideas about gender were evolving at this time. What was happening after World War II, what did we see with genders?

TAYLOR PETREY: There were sort of two kinds of things that were happening simultaneously after World War II. On the one hand, many women had gone to work during World War II because the men were off fighting. And so there had been a kind of early feminist awakening, a liberation, that women had newfound freedoms, financial independence, marriages taking place a little bit later.

So we had a kind of proto-feminist thing, and then a big backlash after World War II ended where there's a large effort, not only in the Church, but in American culture, to kind of reinstitute patriarchal authority in the home, to give men economic advantages over women, and so on.

And so there are these two competing things that are happening, which eventually erupt in the 1960s feminist movement, which is calling out the domesticity that was being imposed on women during the post-World War II era as really quite constraining. And so women start to want to get jobs and get higher education and delay childbearing or have help in childbearing and child raising, and expecting husbands to contribute more to home life.

So there are all these kinds of cultural conflicts that are happening in the 1950s, 1960s, 1970s. And the Church finds itself really right in the middle of these large cultural wars.

BLAIR HODGES: I was really struck to see you point out that, as Latter-day Saints have talked about men's role in the home, as this sort of presider in the home, it in some ways actually kind of encroached on what was typically understood to be a woman's sphere, and that there were these interesting little power struggles or power shifts that were happening within the home between men and women.

TAYLOR PETREY: It's common to think that the gender role expectations during this time period were that men were working out of the home and that women kind of had control in the home, that they were sort of the head of the household. But really, you see Latter-day Saints very wary of even giving that much control to women.

That sort of resurgence of patriarchy in the Church insisted that men actually be the leaders in the home as well. Men's authority was really such that it was not only outside the home, but also in the home. And so there were several programs put into place to sort of reaffirm men's leadership in the home.

Just one example is the Family Home Evening, which is really kind of rejuvenated, if not really invented, during this time period with the explicit goal of making sure that men are in charge of the home. Men are supposed to be organizing Family Home Evening. And it comes as not much of a shock to many Latter-day Saints, but even back in the 1960s, it turns out that the wives were the ones who were doing all of the work.

BLAIR HODGES: Right.

TAYLOR PETREY: And, you know, very soon after this, I think within a year or two of the program, again, Spencer W. Kimball says, I am shocked that there are some men who are letting their wives decide who gives the prayers in family home evening, you know, men, you've got to take these leadership roles. And so you know, a lot of the programs of the Church are meant to kind of make sure that men are in charge in all spaces of life.

BLAIR HODGES: We see in this period, as you highlight, this increasing emphasis on this idea that men “provide” and that women “nurture,” this separation of roles and men as the head and women as the heart of the family.

I hear less of that of that idea, the head and the heart, I feel like I don't hear a lot about that one. But obviously the providing and nurturing thing is still going strong within Mormon culture.

TAYLOR PETREY: That's right. That sort of head and heart language was one that was often repeated, assigning rationality and decision making to men, and nurturing and comforting and feelings to women. You know, they sort of were assigning these gender roles in that very language of attempting to describe them.

You're right, I think that definitely we see a walking back of that. And one of the changes that, you know, I'm sure we'll talk about in a little bit is the rising changes of the culture of the Church members, that is really kind of insisting on and expecting more egalitarian relationships. And so we start to see some further and further accommodation towards that kind of egalitarian impulse to sort of stand side by side with the kind of patriarchal order of marriage as is being taught.

BLAIR HODGES: Yeah, and this chapter also has something that really caught me off guard. Mormon theology about the origins or the root of sex and gender were actually still up for grabs during this period. So you're looking at different church leaders teaching different things about where sex and gender originated.

And so as I said, it seemed like an open question here, we have different views. Talk about some of those different views and what they looked like during this period.

TAYLOR PETREY: You know, I was really struck by this part as well. And one of the research questions I had when I first started the book was to understand the history of the doctrine that gender is an eternal characteristic. Latter-day Saints teach this, and I'm sure we'll talk a little bit more about it down the line, but it becomes an official doctrine of the Church that gender is eternal.

But it turns out that not that long ago, Latter-day Saint leaders actually had a very different view, thinking that gender was quite contingent and unstable. There are a number of different places where we see church leaders—most notably Joseph Fielding Smith, one of the most prominent and important Church leaders and intellectuals of the Church in the 1950s and 60s—putting forward this idea that before we were born it wasn't necessarily the case that we were male and female, that we maybe had some choice or discretion in the matter, and after we die it's not guaranteed that we'll be male or female, either. Only those at the highest levels of the Celestial Kingdom will be male and female.

And I think that, you know, in some cases, both of these are a little bit funny. But they were dealing with a kind of similar issue around the hierarchies around gender as they were around race. And this is again where I want to bring race back into the conversation. There's a talk given in the 1960s that says, “well, why don't women have the priesthood?” And this is the same question, of course, that people are asking about people of African descent, why don't people of African descent have the priesthood? And the answer that many Latter-day Saints had been giving in the 1960s around African descent was that something happened in the pre-existence, the choices that people had made in the pre-existence sort of determined these racial lineages, and some racial lineages were going to be given the priesthood and others were going to be denied it. And so if you were descended from that, it was because of choices that you had made in the pre-existence.

Well, Latter-day Saints apply the same logic to the hierarchy between men and women. And they say, well you must have made some choice in the pre-existence to decide that you were going to be a mother, and others decided that they were going to be priesthood bearers. And so they were kind of saying some sort of explanation for the hierarchy couldn't be because God imposed some sort of unjust hierarchy, but rather that it was the result of our own choices, our own agency.

So they were kind of solving that problem of women not having the priesthood in the exact same ways that they were dealing with race. And then after death—you know, one of my favorite stories about Joseph Fielding Smith is that he's responding to letters from members of the Church, for many decades he did this, they were a column that he would do, but then they were compiled in his books, The Doctrines of Salvation and so on. And one of these letters, somebody asks him, well aren't all those unrighteous, unmarried people just going to be having illicit sex in the afterlife, right? If they were so bad to not merit the highest levels of the Celestial Kingdom, aren't they of course just going to have sex all the time, you know, what's going to stop them?

And he says, they're not going to be male or female, they're going to be genderless in the afterlife. And that's why they won't be able to have sex. So he kind of solves the problem of a potential for illicit sex by just getting rid of sexual difference entirely for, at least, the vast majority of human beings. He says most people are going to be in this category, are going to be neither male or female in the afterlife.

And so this notion that this was sort of a settled doctrine and had always been a settled doctrine that gender was eternal turns out to not really be true. The most senior leaders and some of the most influential leaders of the Church during this time period did not believe that at all.

BLAIR HODGES: One thing I would ask is, [laughs] I remember hearing about—I remember reading this actually—I think the first time I read this was probably as a missionary, I was reading his Answers to Gospel Questions and came across this one. Wouldn't it also be the case, though, that they just didn't have genitals. So they would still be men and women, they just wouldn't be able to do anything about it.

TAYLOR PETREY: Well, that's one possible explanation. And some people who I think try to soften what he's saying have tried to put that forward. But he actually says they will be neither male nor female. And really there, he's actually quoting scripture to make that argument. This isn't just something he's making up, he's quoting Galatians 3:28.

BLAIR HODGES: Right.

TAYLOR PETREY: Which says that “in Christ, they should neither be male nor female.” And so he's not only suggesting that they don't have genitals, but actually that their sexual difference entirely is erased.

BLAIR HODGES: So you're seeing these different views. We have different BYU religion professors saying that there's no primal intelligence that had a gender or sex, you have Assistants to the Twelve giving talks in General Conference talking about making a choice about their sex, and then you have people like James Talmage, who's teaching that gender is eternal, that male and female have been such from the beginning.

So there's all these different ideas. It was striking to me to see that it was kind of up for grabs, and to see that there were just particular voices that kind of carried the day on this so that it became mainstream Mormon doctrine.

TAYLOR PETREY: I definitely want to say that there have been Latter-day Saints who have believed that gender is an eternal characteristic throughout time, and you can look to different periods. I don't think that that was the dominant view in the 1950s and 60s though, as much as I looked to try to understand this time period.

First of all, there aren't a lot of statements on it at all. It wasn't a doctrine that they were really particularly worried about or thinking about, but the statements where you do see it are, again, along the lines of a kind of gender fluidity in the afterlife and in the pre-existence and so on.

And, you know, again, it's hard to say what was the majority teaching of the Church during the time period, we just don't have surveys, for instance, of General Authorities.

BLAIR HODGES: [laugh] Right.

TAYLOR PETREY: But when people did talk about it, the kinds of things that they were saying were not along the lines of “gender is eternal.” I think the notion that gender is eternal re-emerges in the 1970s and 80s as another solution to a different problem around gender that the 1950s and 60s saw, you know, a different answer for, “well, it was choice in the pre-existence,” or “it's contingent, you're going to lose it.” And those doctrines sort of lose popularity or favor among senior Church leadership and the doctrines of the eternalness of gender reemerged during that later period.

Homosexuality becomes a focus

BLAIR HODGES: Ooh, that's a good teaser for a little bit later on in the interview. We're talking with Taylor Petrey today. He's associate professor of religion at Kalamazoo College and also the editor of Dialogue: a Journal of Mormon Thought. We're talking about the book Tabernacles of Clay: Sexuality and Gender in Modern Mormonism.

Alright, let's go ahead to chapter two here with the little the pun in your title, “Sodom and Cumorah,” I suppose you couldn't resist that pun.

TAYLOR PETREY: [laughs] It was too good. Somebody had given it to me a little late in the process and I was like, I gotta name the whole chapter that, it was too good.

BLAIR HODGES: Yeah, you're looking at how the Church understood same-sexrelationships from the 1950s through the 70s. And the history here shows the Church actually made some pretty big shifts in how it understood homosexuality. Let's talk about those shifts.

TAYLOR PETREY: I put forward—maybe, I think, totally intuitive to me, but maybe a little bit controversial—the idea that homosexuality is actually invented in the Latter-day Saint tradition in the 1950s. And what I mean by that is that there's a shift from thinking of sodomy as a kind of set of practices that one might engage in, to homosexuality as being an identity, as being a mental condition, and specifically a psychological condition that people might suffer from as Latter-day Saint leaders might have understood it.

And so we see a shift away from thinking about this as a set of forbidden practices, to being a whole identity, a whole kind of way of being in the world, that Church leaders begin to pay attention to and regulate. And so there's really a pretty dramatic shift away from thinking about punitive treatment for people who might engage in same-sex intercourse to a whole apparatus for treating people's psychological conditions in order to provide them what they were promising at the time was a cure for the malady of homosexuality.

BLAIR HODGES: You note a shift from kind of moral discourse to psychological discourse, this idea that these are sinful actions that a person undertakes, that maybe they're tempted by Satan to do, to this being like a psychological condition that had particular causes, and also then had particular cures as well. Nationally, what was happening in talk about homosexuality? How was America kind of understanding homosexuals at this time? In the 50s specifically?

TAYLOR PETREY: Well, you know, before that, before the 1950s—just a little bit of background on this—the notion of a kind of psychological cure for homosexuality was actually the sort of progressive view. Progressives had kind of latched on to Freudian psychology and sort of had seen this idea of like, “oh, you know, look at these poor people who are suffering, and we can provide them help with psychological care, with a modern science of psychology and psychoanalysis,” you know, and so those ideas had kind of emerged in liberal Christianity originally, whereas conservatives were still kind of using the moral discourse of condemnation and so on, rather than sort of pastoral outreach and help and so on.

BLAIR HODGES: Like, God will destroy them kind of thing?

TAYLOR PETREY: That's right. In the 1950s, there are a lot of things happening to change broader American culture with respect to homosexuality. First of all, you know, many men had had sex with other men during the war. They come home and are moving to big cities, there's emerging gay subcultures that are happening there. The same thing, as we mentioned, among lesbians is happening too. Women are having more freedom, the fact that they were working and that they weren't working with men during the war, again, also sort of changes and contributes to the rise of more and more of these subcultures. They existed in cities long before this, of course, but, you know, we really see a larger rise and organization of these communities happening during this time period.

Meanwhile, conservatives like Latter-day Saints are looking to psychology and this Freudian psychology as a solution to these problems more and more, whereas liberal Christians begin to say, wait a second, maybe we actually shouldn't be thinking of this as a sickness or as an illness. We should be listening to these communities who are telling us that they're not sick, they're not ill, they don't need our help, and maybe we should just let them be themselves.

Conservatives are sort of now glomming on to those ideas of psychological cures. And these are really contested issues within the psychological community during this time period—the secular psychological community. By the time we get to the early 1970s, we see a pretty quick about-face where the psychological associations finally de-pathologize homosexuality officially by vote in their organizations to say we're not going to consider this a mental illness anymore. Latter-day Saints and other conservatives reject that sort of “secular” assessment and see it as a betrayal of the morality that they really had held on to. And we see that mingling of the moral evaluation with a psychological evaluation and a kind of revival or attempt to hold on to some of those now-abandoned theories of homosexuality as a pathology, as a mental illness. And, and so the Church really fully leans into this psychological view now.

The decline of civilizations

BLAIR HODGES: And you also note, there's this decline of civilization narrative that starts. The story that starts to be told as professional associations and others are coming to see homosexuality differently, not as a failure, then there's this moral panic of “Wait a minute, if this becomes accepted, civilization itself is going to be destroyed.” What's this narrative about?

TAYLOR PETREY: Just as we see a sort of psychological assessment of homosexuality as a mental illness, we're also seeing a kind of pseudo-sociological theory of sexual misconduct as a social illness. And there are all of these kind of pseudo histories that are being written and a whole intellectual history here of conservatives making this argument that patriarchy and anti-homosexuality are necessary for the survival of civilization. And these sorts of civilization-level assessments are really powerful in the 1950s and 1960s and beyond, in part because the United States is engaged in an existential battle in the Cold War. And every kind of advantage the United States can have in surviving and thriving in its battle against an existential foe—

BLAIR HODGES: The Communists!

TAYLOR PETREY: —The Communists!—becomes really important. So the family and these conservative teachings about sexuality are being framed and sold as necessary for national and civilizational strength and survival. And there are all of these myths that are being told about, if look at the Romans, they fell because of their sexual profligacy. And if you look at the Greeks, they did the same thing, right? And, you know, all of these efforts to kind of see sexual practices as geopolitical—as having a sort of geopolitical interest.

BLAIR HODGES: And so Latter-day Saint leaders hop on with this narrative as well, and it actually becomes even more existentially threatening, because not only could the fall of civilization happen, but also it sort of could destroy the plan of God, right? So it's like the ultimate civilizational decline story.

TAYLOR PETREY: Yeah, you know, one of the things that they're most critical about, again sort of blending their anti-homosexuality with the kind of discourses around patriarchy—and again, I don't mean patriarchy, I mean, I'm using the way that they're using it.

BLAIR HODGES: Yeah, let's unpack that. [laughs] Yeah, that word has got a lot behind it.

TAYLOR PETREY: They're talking about the “patriarchal order” as the divinely instituted thing. They're saying it all the time, “we believe in a patriarchy,” and they mean it literally, you know? Sometimes, you know, they mean a benevolent patriarchy, but they're really talking about patriarchy, about male rule. And one of their concerns sort of jointly around anti-feminism and around anti-homosexuality is this idea that homosexuality is not reproductive. And you know, they opposed birth control during this time period very strongly, right? They were very pro-natalist. Church leaders were very pro-natalist.

BLAIR HODGES: Pro-baby.

TAYLOR PETREY: And they saw, in homosexuality, a threat to the production of children, to reproduction, just in the same way that they saw it in abortion and in birth control and other kinds of things. And they worried that non-reproductive sex would become so tempting and so interesting to people, including homosexual sex, that if there weren't social and legal sanctions against it, that within a single generation everyone might be just exclusively practicing non-reproductive sex, including homosexuality, and there would be no more children anymore.

And this is something that they repeated again and again and again, this idea of a kind of national suicide, that would happen if homosexuality were permitted. And what I've always found a little bit funny about this is that they seem to be suggesting that homosexuality is extremely alluring, is extremely tempting that everyone would do it if they could, you know? [laughs]

BLAIR HODGES: And, and you're not exaggerating, either like that. I mean, we chuckle about it, but you lay it out in the book like this, this was real.

TAYLOR PETREY: Yes. They really worried about this and constantly warned against it.

BLAIR HODGES: This is a central tension that you bring up, I think, throughout the book. There's this conflict within Mormonism itself, about how sex is understood. On the one hand, you have so many leaders talking about what scholars would call “gender essentialism,” this is the idea that there are these natural, fixed, differences between men and women, between male and female. These are essential things about different people. But then on the other hand, they've also taught that sexual difference has to be nurtured, has to be guarded, because it's changeable, it's malleable.

So on the one hand, it's essential. On the other hand, it could change at the drop of a hat. And this seems like a paradox here.

TAYLOR PETREY: I think that's a great way of putting it, that's exactly right. You know, on the one hand, they say that it is fixed, it's durable, you know, you can't change it, it's God. God has put it in place, or nature has put it in place in this way.

And on the other hand, it's so fragile that permitting homosexuality to be legal, allowing women to wear pants at one point was very controversial, if women went to work they would become lesbians, because they would learn the aggressive ways of the business world, and that would make their desires shift toward women, you know.

BLAIR HODGES: Right.

TAYLOR PETREY: And again, we look back at these things and we’re like, they couldn't have been serious, but no, they were dead serious. This is really what they were teaching.

BLAIR HODGES: I still think there are some people that have these views, actually.

TAYLOR PETREY: Yes, yes. Again, like around those issues around race, some of these older views definitely still linger in the LDS culture. So I just wanted to try to point out again, sort of looking at this idea of gender as being fixed, as gender being eternal, and an eternal characteristic, trying to uncover the ways that Church leaders saw it as so fragile, and also, as you said, as malleable, as something that could and should be shaped as conditioned and cultivated.

Shifting from moral to psychological solutions

BLAIR HODGES: You point out that that sort of threat can actually become the solution here. So during this time period, and putting it within Christianity, Christian salvation itself was making a shift right now. It was more toward self-realization, like, through Christ you become your true self, you progress, you advance. And Latter-day Saints were picking up on these same sort of progressive Christian ideas. And so the fact that sex was malleable also meant that you could fix it, that you could be cured. And so this is a shift we're seeing in Latter-day Saint discourse here with Spencer W. Kimball's Miracle of Forgiveness book. Talk a little bit about that.

TAYLOR PETREY: Yeah. So Kimball really was a part of, not necessarily the kind of professional psychological perspectives that were kind of dominating his day, but the popular psychological perspectives that dominated in his day. He cites a number of leaders of what we now would call the “New Thought movement.” And the New Thought movement was this idea that you could sort of control your destiny by controlling your thoughts. And so he was very invested in this sort of idea.

And we see this happening in other popular movements that are coming out, you know, The Power of Positive Thinking by Norman Vincent Peale is a book that's published in this time period. And it turns out that Norman Vincent Peale and Spencer W Kimball are friends and know each other, you know, and so Spencer W. Kimball is kind of drawing on these ideas of the power of positive thinking. And they influence his book, The Miracle of Forgiveness, for instance. It's very much about disciplining the mind in order to discipline one's practices and shape oneself. And I like the way that you put it, that there's this sort of broader change that's happening in American Christianity of this time period of self-actualization, self-realization, as being the kind of dominant way that Christians come to talk about, and absolutely Latter-day Saints are participating in that movement as well. And seeing the kind of cultivation of the self through a regulation of sexual desire as an especially powerful way of doing that.

BLAIR HODGES: And you see Spencer W. Kimball, on the one hand he'll be speaking incredibly negatively about homosexuality, referring to people as menaces and using this very, very harsh language. And then on the other hand, he's also asking Church members to treat them with sympathy. He seems to be torn between sort of being disgusted and feeling sympathetic.

TAYLOR PETREY: Yeah. You know, really more than any other Latter-day Saint during this time period he met with and counselled with thousands of gay Latter-day Saints during the 1950s, 60s, and 70s. I would wager to bet that nearly every gay Latter-day Saint during that time period met with Spencer W. Kimball, you know? [laughs] He was sort of out and about on the town and working with everybody that he could.

And he kind of developed these theories around it. On the one hand, a deterrence model, right? A very harsh preaching against homosexuality, as you said, very strongly worded terms against it. And on the other hand, this idea of a kind of love and sympathy, the sort of “love the sinner, hate the sin” model. And in fact, he even uses that language himself too. And, you know, as you said, there's a little bit of contradiction or tension in here. But his perspective is that what it means to love the homosexual is to try to change them, is to try to make them give up their homosexual ways, to come back to live what he calls the normal lifestyle of heterosexuality. And offer, again, this psychological analysis that “this is a disease”—he uses a lot of the language, not just that social language as you said around menace and so on, but really disease, illness, and this idea of the bishop or himself as the physician who's providing a cure through repentance.

And so yeah, we really see sort of those two sides of him pretty starkly in that book and but all throughout his preaching.

BLAIR HODGES: You also note how he's adopting, as you've kind of suggested, he's adopting the language of secular authorities here. So we see professional organizations start to appear. They're trying to treat homosexuality, to cure homosexuality through secular means, and through positive thought, but also through therapies. And the Church is jumping on that bandwagon here. Even at Brigham Young University, the Church's university, they start a Values Institute. Give us just a little bit of history on that Values Institute and how that went.

TAYLOR PETREY: Yeah, so in some ways, the slight predecessor to the Values Institute is LDS Social Services, which is the welfare or welfare services, it kind of changes names, sometimes called Family Services, sometimes Social Services, sometimes Welfare Services. But in the late 1960s, the priesthood takes over this organization from what was formerly run by the Relief Society. And they install a number of psychologists to kind of run it.

Psychological care and treatment is about to become a very important part of church practices. Bishops are sort of saying, listen, we're not trained psychologists, we're not trained therapists, we need a little bit of help here. And so the Church is offering these new services. And they put in place psychologists who are also again trained in the 1950s and 60s, and those ideas that had once been dominant views of homosexuality as a pathology, those psychologists are now running LDS Social Services, and providing psychological care through LDS Social Services to people who are quote unquote, “afflicted” with this mental illness, with homosexuality.

But they're finding that even that in the 1970s, is, you know, not quite sufficient. They're not really effective in the ways that they thought that they were going to be. And as I said, the secular authorities on psychology had actually changed their mind on this and were abandoning these ideas. And so those same psychologists at the LDS Social Services go to the Church and say, you know what? We need a research institute that can really kind of establish the authority of these ideas that homosexuality can change, that homosexuality is a pathology. And the Church funds this Values Institute, as it's called, it has a longer name, but that's what it comes to be known as, in the 1970s during President Oaks's tenure as president of BYU.

BLAIR HODGES: He's now a Latter-day Saint apostle, for people who aren't Latter-day Saints.

TAYLOR PETREY: That's right. That's right. Well known. Yeah. And they kind of are working on this idea of, they're going to write a book, they're going to publish it with a secular press that's going to prove these ideas of sort of apologetics for Latter-day Saint teachings through secular means, without mentioning Latter-day Saints at all. That project doesn't really take off in the way that they expected it to. But it is sort of, in some ways, a symbolic first failure of the attempt to sort of vindicate LDS teachings through secular means—LDS opposition to homosexuality—and the effectiveness of reparative therapy and change therapy and so on.

BLAIR HODGES: This includes electroshock therapy, right?

TAYLOR PETREY: The Values Institute isn't involved in that. That's happening in the psychology department. There are overlaps between members of those two groups, but the aversion therapy or electroshock therapy that is happening at BYU—a little bit out of date and old-fashioned at that time period, but had been practiced in psychological communities for decades to treat homosexuality before that—was taken up for about a decade or a decade and a half, at least, at BYU, too, as one of the things, but it wasn't necessarily associated with a values Institute.

BLAIR HODGES: Okay, interesting. That was when President Oaks was there, right?

TAYLOR PETREY: That's absolutely true. It was happening in the psychology department, you know, again, supervised by faculty members, not necessarily at the level of administration. But it was a somewhat well-known program on the campus because the Honor Code Office and BYU police would refer people to that program for treatment that had kind of gotten caught up in their surveillance.

The rise of supportive groups

BLAIR HODGES: You also note the rise during this period of some Latter-day Saint groups that are specifically for gay people at this time.

TAYLOR PETREY: Just like we see the rise of Latter-day Saint feminist movements in the 1970s, we also see the rise of Latter-day Saint gay and lesbian organizations in the 1970s that are attempting to find space or accommodation for gay members of the Church. And I explicitly say it's just gay members of the Church at the time here, they're not really thinking of trans and intersex issues yet. Those are gonna come later.

But in the 1970s, gay men and women are beginning to organize. They're writing letters and pamphlets and meeting together. You know, probably the most important organization that comes out of this period is Affirmation, which was originally an advocacy organization to change the Church's teachings on homosexuality to allow for same-sex relationships and to allow for homosexuality all the way back in the 1970s.

BLAIR HODGES: How did how did that pan out?

TAYLOR PETREY: Affirmation has had sort of numerous iterations of its identity, sometimes taking, again, an approach to sort of change the Church, sometimes taking a very oppositional stance against the Church. And, you know, it kind of tries to mediate between those two identities among its membership and leadership over the last several decades to find their space, their voice.

BLAIR HODGES: I should point out, too, a lot of times, we're talking about homosexuality throughout this section, the Church was more focused on men than women, right? Were lesbians on the radar here very much, or am I wrong about that impression?

TAYLOR PETREY: Almost never. There are a few, a few things of saying, you know, “and women sometimes suffer from this too.” But almost exclusively, when Church leaders are talking about homosexuality publicly, they're talking about men.

You know, there are, I think, a number of possible theories for why they're not talking about women. Maybe women aren't coming to them to confess. Maybe, you know, they're less interested in those kinds of things. But for men, yeah, this is really, when we talk about homosexuality during this period, how the Church framed their own interests in it. They saw it almost exclusively in terms of regulating and curing men.

BLAIR HODGES: And you also mentioned trans issues, are they starting to get any attention during this period?

TAYLOR PETREY: There is a little bit of popular discussion about trans issues in American culture, again, all the way back to the 1950s. The first transsexual surgeries were happening in the 1950s. And these were front page news. And there were celebrity trans people in the 1950s. And so church members and leaders certainly were aware of these kinds of things. But we don't really see public comment on it until the 1970s.

And it's often thought of—that is transsexuality is often thought of—as a sort of extreme form, or the logical outcome of homosexuality. You know, they thought of homosexuality as becoming like a woman. And becoming trans would then be sort of the logical outcome of that, you know, the full feminization of the male homosexual. And so we see again, a sort of conflation of trans and homosexual issues happening in the 1970s. And that's the way that they talked about it and thought about it.

The church encounters egalitarian feminism

BLAIR HODGES: That's Taylor Petrey. He's associate professor of religion at Kalamazoo College and editor of Dialogue: a Journal of Mormon Thought and we're talking about the book Tabernacles of Clay: Sexuality and Gender in Modern Mormonism. There's a ton more in that chapter that people can check out in the book.

Let's go ahead to chapter three here, “Politics and the Patriarchal Order.” In this chapter you're talking about gender roles more specifically, and how they were seen for men and women in the sixties and seventies. The Church is now confronting what scholars have called “egalitarian feminism.” Give us a little bit of info about that.

TAYLOR PETREY: Yeah. So, you know, the broader feminist movement that's happening in the 1960s the 1970s, is challenging gender roles. It's challenging the ideas of the family. It's challenging limitations of women in the workplace and so on. And feminists during this time period are pushing for egalitarianism—not just equality before the law as the first wave of feminism had kind of put forward, that women should have the vote, they should have an equal vote and so on. Here, we're really talking about a shift in cultural values, and in many cases legal values as well, where women should be treated equally in the home, should be treated equally in the workplace, and so on.

And, you know, you start to see these movements happening in the Church of, you know, women are saying, hey, we're in a patriarchal system here and we would like to be treated equally we would like to—and in some cases, there are some women who are pushing for the priesthood. But most feminists were just pushing to maybe have the opportunity to go to work, or to, you know, have their husbands pitch in more at home, or to have an equal say over the finances at home. And so some maybe more modest sort of reforms in this egalitarian movement.

So the egalitarian feminist concerns are really, again, about sort of reforming the institutions that that women and men found themselves in simultaneously that were oftentimes privileging male voices and concerns.

BLAIR HODGES: How did the Church and Church leaders accommodate to these movements, because Mormonism, as you point out in the book, didn't simply reject these social changes and these social pressures. They also made some accommodations here.

TAYLOR PETREY: In some respects, in the 1950s and 60s, the Church is strictly following what they would call “the patriarchal order.” And they're sniffing out all of these places where there are actually places of women's equality or even women's power, and they're taking them away.

So the Relief Society is greatly diminished, for instance, during this time period. We mentioned already the way that the priesthood sort of takes away the social services arm of the Relief Society, for instance.

BLAIR HODGES: Their budget.

TAYLOR PETREY: Their budget, their magazine—

BLAIR HODGES: Their publications, yeah.

TAYLOR PETREY: the Relief Society is really—yeah, loses a lot of power, because there's an ideology that the Church needs to be patriarchal, and it's actually failed and not being patriarchal enough. And so there all of these reformers who are making the Church more patriarchal, during the 1950s and sixties. There's a big stretch of time where women aren't allowed to pray in sacrament meeting, because it's thought to be a priesthood function, a priesthood meeting.

And so there are a number of feminists who are coming, and non-feminist women, who are sort of saying, wait a second here, not that long ago we had some power here, and now all that's gone, you know.

BLAIR HODGES: Yeah.

TAYLOR PETREY: And so there are there are various reform efforts to kind of help the Church be more friendly to a sort of very moderate, very modest feminist concerns in some cases, but they are also much more quote-unquote, “radical” feminists who are calling for full equality in the Church, who are calling for women to be ordained to the priesthood, because there are other women in other religious traditions during this time period who are obtaining ordination in their churches. There's a women's ordination movement happening all across American Christianity. And, you know, Latter-day Saint women are seeing women preachers, and women pastors, and women priests in different religious traditions, and saying, why not us also?

A sexual revolution within Mormonism

BLAIR HODGES: It was also interesting to see during this chapter where the Church would talk about how it was different from the world. The world would be this thing against which the Church was compared. The world does this, the Church does this. But there were these examples where the Church followed right along with “the world.” And one important example, I think, in this chapter, is the role of sex itself, sex between heterosexual couples, that previously it was talked about as being something that was for procreation. The purpose of sex was to have children. There was a shift here. The role of sex expanded here significantly.

TAYLOR PETREY: Yeah, there's really what I call a “sexual revolution” in Mormonism in the 1950s, 60s, 70s, and 80s around birth control. Birth control reshapes American culture in general, and there's a larger sexual revolution of course that's happening in American culture, where sex outside of marriage is much more common, recreational sex becomes much more possible and safer for people to engage in. And you’ve got everything from the normalization of pornography in Playboy, you know, broader shifts that are happening in American culture. And Latter-day Saints are oftentimes very resistant and hesitant and oppose those cultural shifts.

But at the same time, just like Mormon women are calling for more egalitarian marriages, just like they're expecting of their non-Latter-day Saint peers. There's a kind of broader shift that's happening among sexual attitudes among church members. And where Church leaders were saying, “sex is for the sole purpose of procreation, you should have as many children as possible,” there are all kinds of social and economic pressures that are pushing people away from that ideal. And Latter-day Saints are actually using birth control in contradiction to the teachings of the Church leaders. And so Church leaders really start to soften some of those teachings until they ultimately abandon them in the early 1980s officially, by saying now that birth control is a private choice, it's not something that the Church is going to get involved in anymore.

But that really kind of represents this culmination of a new ideology of sex that emerges in the Church. Where it used to be only for the sole purpose of procreation, it now is for the purpose of spousal bonding as well, and Church leaders begin to talk about sex, not in terms of procreation, but in terms of the emotional dimension to sexuality, of this relational dimension of sexuality. It suddenly sort of covers a much broader sphere of things than it had previously done for earlier Church leaders.

And so I tried to situate this redefinition of sex in a sort of broader context of a sexual revolution in America, but also a sexual revolution that's happening in the Church. And birth control is the most obvious place where that's happening.

The politics of proclamation

BLAIR HODGES: And that kind of takes us up to a really important Mormon document called The Family: A Proclamation to the World. This was published in 1995. And this kind of laid out the Church's stance on what marriage is, what family looks like. It emphasizes marriage between a man and a woman. It talks about roles that men and women have within families and responsibilities that they have.

And it's pitched towards society. And that wasn't completely unusual then because as you note earlier, the Church had already been getting involved politically now. It sort of saw the need, not just to preach morals, but also to talk to society and to talk about legal issues as well. Was that a big shift for the Church to start getting involved in legal cases?

TAYLOR PETREY: Yes. You know, I mean, certainly the Church had a long history of getting involved in local politics, certainly in some respects national political issues that directly affected them around plural marriage, for instance. But we see the Church sort of joining a coalition of the Religious Right that's emerging as a cultural force during this same time period.

And one of the places where the Church is finding agreement and allies with other religious groups, like Conservative Catholics and Evangelical Protestants, is on the politicization of the family itself. And these are larger cultural issues that are happening, again, around the feminist movement, around abortion, around birth control laws even, certainly around homosexuality. And there becomes a kind of reorientation of the political landscape, where these religious groups, including Latter-day Saints, strike up an alliance and a coalition to put forward conservative social policies on these issues.

In some respects, these grew out of previous people who had opposed racial integration, these same groups are reconstituted now around gender and sexuality issues. And that becomes a much more effective strategy than their opposition to racial integration a few decades before that.

But you know, the Church sort of finds that these people that used to be bitter enemies—Catholics, Evangelical Protestants, and in many cases were continued rivals, religious rivals—are now willing to meet with them and willing to work with them on political issues. So it becomes a way for the Church in some ways to integrate into broader American culture by joining on with these political culture wars.

So as you mentioned, the Proclamation, as it's sometimes called, The Family: A Proclamation to the World, is in some respects, a sort of outgrowth of the Church's opposition to the Equal Rights Amendment in the 1970s. And as the Church is now finding itself in the middle of the 1990s, its opposition to same-sex marriage movements that are just beginning to pop up in the national landscape. And the Church says, let's bring the old gang back together again that opposed the Equal Rights Amendment, we're all going to get back together now and we're going to oppose same-sex marriage. And again, this becomes a way for the Church to sort of join hands with other people who might in other cases, be adversaries, to have these new allies.

BLAIR HODGES: Yeah, I remember, during the Proposition 8 stuff in the 2000s hearing church members remark that, you know, it was amazing that Church leaders had put the Proclamation out in 1995. Sort of the idea that was prophetic, that it kind of saw into the future. But your research suggests that it actually was a direct outgrowth of political battles that were already being waged as early as 1993.

TAYLOR PETREY: Certainly in the in the public sphere in 1993. Hawaii is the first case to really—the first state to really sort of consider legalizing same-sex marriage through a bunch of court battles that were happening during that time period. But you know, there are same-sex marriage movements dating back to the 1970s, and even in the Church's literature opposing the Equal Rights Amendment in the 1970s one of their major arguments for opposing the Equal Rights Amendment is that it might lead to same-sex marriage.

So that's already on their radar many decades before. There were efforts to have same-sex marriages be legalized in the 1970s. And in the 1980s, Elder Oaks—who we had talked about as the former president of BYU—as a new apostle, he actually writes a memo explaining “listen, same-sex marriage is coming down the pike.” This is a decade before it actually happens. But they knew that this was going to be an issue at some point, because everybody who was living during that time period sort of said, “ah, this is the extreme case that might happen at some point.” So, you know, everybody, everybody sort of saw same-sex marriage as the inevitable battle that was going to happen at some point.

BLAIR HODGES: Do you think the Church's approach was much different during these—like Proposition 22, Proposition 8, these anti-same-sex marriage bills—how was the Church's approach different toward these than it was like with ERA? Were there any differences in its overall approach?

TAYLOR PETREY: In many ways it adopted a very similar strategy. They attempted to kind of find minor ways of accommodating social change. They wanted to emphasize that they believed in equality, that they believed in the dignity of their opponents, but at the same time resisted any social change as something that they painted as very dangerous for society, and so on.

So we saw them describe the ERA in terms of civilizational collapse, civilizational decline, those narratives that we talked about. And that same language sort of reemerges when they talk about same-sex marriage—it's also going to lead to civilizational decline, it's going to lead to gender confusion, it's going to lead to children not knowing about gender roles, and so on. And so they're very much kind of replaying some of the same scripts in both cases.

Theological and psychological shifts

BLAIR HODGES: Alright, that's Taylor Petrey and we're talking about Tabernacles of Clay: Sexuality and Gender in Modern Mormonism.

Your next chapter is called “The Death and Resurrection of the Homosexual,” this is chapter five. And from the year 2000 up to the present, your book argues, the Church changed in some significant ways about sex and gender. And you break these changes up in some different categories I wrote down here.

You say that there were some theological changes, linguistic changes, psychological transitions, and political transitions. I thought we could just spend just a quick moment on each of these, I want people to check the book out to really dig in, but let's just spend a moment. Begin with theological. What's an example of a big theological transition that happened from the year 2000 to today?

TAYLOR PETREY: One of the teachings that really starts to emerge in in this period is, the theological change is in some respects in response to the failures of the psychological treatments that they had been pursuing for several decades at that point. It turns out that sexuality is very hard to change, and that it wasn't happening in the ways that they had promised in many cases. And so you start to see the Church shifting away from saying that sexuality needs to be cured in this life, to suggesting that, “well maybe it won't be cured in this life, and it can be cured in the next life.”

And so there's this new teaching that emerges of a sort of delay of the cure to after death. This is a slightly dangerous doctrine, because it suggests that when you die, you won't be homosexual anymore, perhaps becoming a method for some people to take their own lives in pursuit of that goal. You know, it's a pretty unpopular doctrine, for a lot of reasons. But you start to see in that doctrine an attempt to deal with, again, a change in their understandings of—perhaps homosexuality is a little bit more fixed than we originally imagined.

BLAIR HODGES: I want to draw a parallel there. I've done research on disability and Mormonism and mine was in the nineteenth century. So during the 1800s, during the time of polygamy, disabilities, birth defects, intellectual disabilities, were thought to be the outcome of immoral behavior by parents and things like this. And Latter-day Saint leaders taught that through a pure marriage practice of polygamy, those things would be done away with, that offspring would be perfected, and you'd see the rise of this strong Mormon race basically.

And, you know, obviously, polygamy didn't resolve disabilities. And so because of the actual evidence at hand, they had to shift that theology. We had to shift that story away from saying that we were going to do away with it on earth—and the solution was the same, it was that in the resurrection these things to be taken care of. I just think that's really striking, especially because we still—I think homosexuality, in church discourse is sometimes lumped in with disability at this point.

TAYLOR PETREY: It directly is, yeah. I mean, Church leaders begin to—they shift away from saying homosexuality is like alcoholism, to start to say that homosexuality is like a birth defect, a disability in some in some ways. And so yeah, I think you're absolutely right to say they're drawing on some earlier teachings in order to kind of reformulate these doctrines of homosexual cures in the afterlife. But it also again signals a shift away from thinking of this as a psychological disorder to being a disability. And that that kind of shift in understanding of the nature of homosexuality brings along with it a whole theological apparatus to help make sense of it.

Linguistic shifts

BLAIR HODGES: Yeah. So that's the theological and the psychological, they’re sort of mingling together there. So that that's an example of how those are shifting during the 2000s. How about linguistic transitions? What is that about?

TAYLOR PETREY: Yeah, so there's a kind of funny history that I discovered that I was really trying to make sense of, over and over and over again, as I was looking at all of these sources, where I mentioned that homosexuality is invented as a concept in the Church in the 1950s. And we see the Church using, Church leaders using, the terms homosexual, homosexuality, very freely during that time period. By the end of the 1970s there's really a kind of emergence of a taboo on the language of homosexual and homosexuality, gay, lesbian, all of these kinds of terms, in part because the Church believes that they might cause the condition. If you label someone as gay or lesbian or homosexual, then that's only going to sort of reaffirm their identity in that way. And so they say, no, don't ever call anybody that. And so they say, you know, “say that they have homosexual desires” or something along those lines.

By the time we get to the 1990s, the Church finally sort of lands on an alternative term: same-sex attraction. And this becomes a sort of substitution for the language of homosexuality, of gay, of lesbian, and so on. And so they're really kind of fighting this, there's a whole ideology behind these terms here.

There's a fascinating thing that happens by the end of the 2000s, where the Church sort of finally gives up what they had once called a doctrine of opposing the language of homosexuality, to say, “ah, okay, you can call yourself gay, you can call yourself homosexual, you can call yourself a lesbian, you can call yourself queer, that's not something that we're going to concern ourselves with anymore.” And so they sort of abandoned the fight over language during that time period. And this happens in terms of the policy changes at BYU, where there's a change to the honor code that allows students to now self-identify as gay and lesbian and queer. And we also see that happening in our broader church communication that's going on during that time period, where they start to—they launch a website called Mormon and Gay, Mormons and Gays, and they start to kind of use that language much more freely in their public communication, whereas before, it was completely forbidden. And now they're saying, “Oh, it's okay.” So there again, that's one of the other major shifts.

BLAIR HODGES: Right. And the line it draws, like, go ahead and identify that way, but don't act on those—right? There's still this very stark line of like, those things are not approved within Mormonism, actual homosexual behavior, same-sex relationships are not approved, but they're allowing for those identity tags.

TAYLOR PETREY: That's right. So you know, whereas I think we could see it as like, there was once a larger circle of what was considered homosexual activity. And what was included in homosexual activity in that earlier period included identifying as gay, using the term homosexual to describe oneself or another person. That was considered a practice of homosexuality that had been forbidden.

BLAIR HODGES: Mmm, yeah.

TAYLOR PETREY: The practices shrink a little bit, and it becomes just sexual exchange, not language anymore. We're not going to police language like we used to. And you're exactly right, that there still is a line there. But I also want to say the language around homosexual activity was considered homosexual activity before, so.

Political shifts and religious freedom

BLAIR HODGES: Right. So that's the shift there. And then the last one was political transitions. What political transitions have you seen during this time?

TAYLOR PETREY: So the Church was engaged in anti-homosexual legislation practices, especially around same-sex marriage, but not exclusively, during this time period. But they start to get a lot of bad press, it turns out, from that. And in some ways people kind of point out. “Well, listen, you've been saying that you don't oppose gay people that you don't oppose—you know, you don't oppose homosexuality in the legal sphere” and so on. But yet, you know, you still have all these discriminatory laws in Utah and so on.

So the Church really kind of takes that to heart, takes that criticism to heart and begins to shift its legal strategy here from one now that they call the Fairness For All, sometimes it's called the “Utah Compromise,” but they say “listen, we want to sort of have protections, legal protections, for LGBTQ people. And we also want to have protections for religious liberty.”

And so the Church shifts away entirely from the sort of civilizational collapse language—if same-sex marriage would happen, if homosexuality was permitted in society—to now, again, sort of shifting to that smaller circle of saying, “no, we just want religious liberty,” which is a kind of a more minor area of concern for them. And so the shift away from family values, from civilizational interests in opposing homosexuality, to “well, we just want to practice our own stuff undisturbed. We want to be able to have, you know, discrimination in our communities, in our religious contexts here that's not going to be overseen by the federal government,” and so on. That's one of the other major shifts in political strategy is the sort of rise of religious freedom as the alternative.

BLAIR HODGES: And what protections exactly does the Church want? Like what would be lost, what religious freedom needs to be protected? The freedom to do what?

TAYLOR PETREY: This is a great question, and I think one that is sometimes confusing to people, including myself sometimes, of what they want, what they mean. What the Church tends to mean by this, when they talk about it, is religious freedom for the institution. And this is primarily around issues of the businesses that the Church owns and runs, the Church or organization itself of course, but also things like the universities that the Church runs as well.

For instance, should the universities that the Churches run allow for same-sex married students to attend? Should they be able to have housing for same-sex students who are married together, for instance? What kinds of laws and regulations should they have to follow for equal protection that other secular universities have to do? You know, should the Church have to do those things as well?

And so the Church is really in some ways looking for a carve out for the various institutions that it runs. When it's talking about religious freedom, they're talking about BYU, they're talking about the businesses that the Church itself owns, to be able to kind of follow their own religious teachings and to be implemented in those places that they have direct control or influence over. They're a little more ambivalent when it comes to like the cake baker, you know? They're sometimes in favor, sometimes saying, “Now, maybe we should make some accommodations there.” But they're not really talking about individual practices so much when they're talking about religious freedom. They're talking about the Church itself as an institution to be able to operate in the way that it wants to.

BLAIR HODGES: I can't help but draw a parallel to segregation, to this idea of “separate but equal” when it came to race, that there were people that wanted to have white only spaces, black only spaces, to maintain segregation as a marker of freedom, of liberty: the liberty to discriminate. And it just seems like a pretty obvious parallel, I'm interested in your thoughts about whether that's a fair comparison and how sustainable it is for the Church to want these protections to discriminate, in effect.